Danilo Moraes de Oliveira, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9918-9277; Tribunal de Justiça de Mato Grosso do Sul - Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. E-mail: danilo.m.o@gmail.com

Wilson Ravelli Elizeu Maciel, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7165-3592; Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS) - Campus Pantanal, MS, Brasil. E-mail: wilson_ravelli@hotmail.com

Arthur Caldeira Sanches, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0859-5574; Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul - MS – Brasil E-mail: arthur.sanches@ufms.br

Fernando Thiago, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7947-0667; Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul - Três Lagoas, MS, Brasil. E-mail: fernando.t@ufms.br

Caroline Gonçalves, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2514-40221;Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul - Três Lagoas, MS, Brasil. E-mail: goncalves.caroline@ufms.br

Abstract

This research aims to verify the existence of segments of the children’s consumer regarding their behavior in the face of the influence of television advertising. Therefore, an empirical, quantitative-descriptive research was conducted with 283 children, aged between 7 and 12 incomplete years old, duly authorized to answer a structured questionnaire adapted for them. Descriptive statistics and cluster analysis were used for data analysis. It was concluded that children's consumers are divided into five distinct groups, with regard to the influence of television advertisements:: "children heavily influenced by food advertising on television", "children moderately influenced by food advertising on television", “children little influenced by advertising on television by food on television", "children not resistant to the influence of food advertising on television" and "children not influenced by food advertising on television".

Keywords: food advertising; television media; segmentation of the children's consumer.

Resumo

Esta pesquisa tem por objetivo verificar a existência de segmentação do consumidor infantil quanto ao seu comportamento frente à influência da propaganda televisiva. Para tanto, foi conduzida uma pesquisa empírica quantitativa-descritiva com 283 crianças de idades entre 7 e 12 anos incompletos, devidamente autorizadas a responder um questionário estruturado adaptado. Para a análise dos dados foi utilizada Estatística descritiva e Análise de Agrupamentos. Concluiu-se que os consumidores infantis se dividem em cinco grupos distintos, no que se refere à influência das propagandas televisivas: “crianças muito influenciadas pela propaganda de alimentos na televisão”, “crianças moderadamente influenciadas pela propaganda de alimentos na televisão”, “crianças pouco influenciadas pela propaganda de alimentos na televisão”, “crianças não resistentes à influência da propaganda de alimentos na televisão” e “crianças não influenciadas pela propaganda de alimentos na televisão”.

Palavras-chave: propaganda de alimentos; mídia televisiva; segmentação do consumidor infantil.

The child consumer has assumed economic importance as it influences domestic purchases, playing a primary market role, in addition to being the future consumer market. Thus, marketing actions focused on the child consumer fulfill their objectives and become effective as long as they are able to profitably attract and retain customers (Kotler & Keller, 2019). Studies on child consumers are fundamental, since there are differences in consumer behavior according to their age group, as Solomon (2016) states.

In order to make promotional messages communicate products efficiently, companies seek to study and understand children's consumption behavior, their way of thinking and acting, which has generated a wave of research on this consumer segment in recent years. (Smith, Kelly, Yeatman, & Boyland, 2019).

Studies on food consumers, and in this case, child consumers, must take into account that consumers do not have unique and homogeneous behaviors regarding their food choices (Lucchese, Batalha, & Lambert, 2006; Landwehr & Hartmann, 2020). It is also clear that advertising for children is not only focused on companies that make and/or sell toys, films and clothing, but also, and with a strong presence, on the food segment (Souza & Révillion, 2012; Carpentier, Correa, Reyes, & Taillie, 2019).

Advertising broadcast on television is widely used in the market and is a preference of companies as a medium of wide dissemination to the public that, - influenced by advertisements with a high capacity of persuasion, has high power over children and young people (Santos & Batalha, 2010; Omidvar et al., 2021).

Norman et al. (2018) point out that children still in the process of social formation have become an easy target for advertisements and these will have a strong influence on the choices of services and products that will be consumed on a daily basis by the family. Advertisements use techniques to stimulate their young consumers and ensure that they become potential consumers.

Consumer behavior is a subject that serves as a basis for the creation and improvement of products by companies, however, specific studies on child consumer behavior, started in the 1960s, are still little explored in Brazil, consequently, the scientific production on this topic can be further developed (Voigt, 2007).

Given this context, in which the child appears as a consumer, the following research problem was raised: Is it possible to segment the child consumer public in terms of their behavior in the face of the influence of television advertising? Through this questioning, the objective of the work was to verify the existence of segments of the child consumer public regarding their behavior in the face of the influence of television advertising.

Market segmentation is characterized as a strategy of grouping consumers, of a certain product or service, in the composition of a homogeneous group. This concept deals with the separation of the market into categories of current and potential consumers, into groups that have similar characteristics, compared to other classes (Bonoma & Shapiro, 1983).

This segmentation provides a foundation for marketing analysis and a better understanding of consumers, helping to create strategies aimed at sustainable production and competitive advantages of the respective markets in which agents operate (Palmer & Millier, 2004; Tonks, 2009).

Through the development of the area of child psychology and the trend of segmentation of increasingly smaller niches by marketing, it led to an environment conducive to the study of child consumer behavior (Chaudhary & Gupta, 2012). In this way, Mirapalheta (2005) argues that this study can lead to relevant contributions to marketing, being necessary to understand the training process and external influences on which children are exposed, so that it is possible to establish more effective marketing strategies suitable for this niche. This is a significant challenge for marketing professionals and researchers (Chaudhary & Gupta, 2012).

According to McNeal (2002) and Kaur and Singh (2006), the child consumer is part of three distinct markets, namely: the primary market, the futures market and the influencer market.

The primary market is considered children's own right, in the sense that they use their own resources to purchase products/services to meet their needs and desires (McNeal, 2002). Still, according to the author, children's consumption capacity shows an interesting growth (average rate of 5.64% per year), highlighting food as the item most purchased by them, making up a third of total expenses.

The future market concerns children being molded to be future consumers, in this way, creating brand loyalty from childhood means that they can have continued sales later. Thus, companies aim not only to make the child consumer aware of their products and their brand, but also that this remains and grows in the child's mind (Solomon, 2016).

As for the influencing market, there is a growing recognition of the importance of children in the decision-making process of purchasing and consumption in the family, in this sense, as they are not only important figures in this, but also vital influencers, especially in terms of food purchases (Suwandinata, 2011).

The evolution of the child as a consumer happened from the moment when the child became more important in society from the 20th century onwards (Gbadamosi, 2017). At the beginning of the 20th century, several transformations consolidated the social relevance of the child and gave rise to the notion of childhood, in which the child needed to receive more care and protection (Gross, 2010).

Despite this increase in the importance of children within the family environment, they only came to be seen as consumers after the Second World War, as they presented size, purchasing power and their own needs (McNeal, 2000).

The child is in front of advertisements and gets to know the brands and categories of products, so it is at this moment that he especially asks for toys, snacks, fast food and dairy products (Veloso, Hildebrand, & Daré, 2008).

Preferences for clothes, music and food, for example, vary according to age, and, based on this, a company can even estimate how much profit it will make over the lifetime of a consumer, which is called the Customer Life Cycle (Solomon, 2016). Children, today considered consumers of almost everything, make companies direct their strategies to captivate them and leverage their sales (Smith, Kelly, Yetman, & Boyland, 2019).

Norman et al. (2018) add that the children's audience attributes a high degree of credibility to products that use animated characters and authority figures and celebrities in their communication. The role of the brand is to develop a mediation between the physical reality of the brand in question and the psychic reality of children (Kelly et al., 2019).

Children look for connections between the character and the product, seeking meaning in the concrete elements presented, such as colors and shapes, in addition to more subjective information, such as values, energy, strength and vitality. Thus, the effective function of the characters is in the identification process, in which the child tries to look like them. Such identification corresponds to the satisfaction of material needs (acquisition of the object) and hedonic desires (feeling of pleasure) (Gbadamosi, 2017; Kelly et al., 2019).

The child's awareness that advertising has the objective of selling products allows for considerations about the child's perception of the appeals made by brands. These show more interest in advertising up to the age of ten, because from this age on, they are aware of the techniques used and the objectives, as well as developing their critical sense, leading to less confidence in advertising. In addition to this, some elements may favor the child's taste for advertising, such as fun advertisements that make them laugh, with cartoons, music that attracts attention - elements that help with memorization -, presence of animals (especially those personified), with action and that value what they believe to be good for their age (Solomon, 2016).

Advertising has some characteristics such as the possibility of market penetration, that is, being repeated several times, it helps the customer to absorb and compare the message; it also allows for improvement in the company's visibility, through the use of artistic elements, such as images and sounds; and it consists of impersonality in communication with the customer, since he is not obliged to keep his attention focused on the advertisement (Kotler & Keller, 2019).

Like other age groups, childhood refers to a socially, historically and culturally constructed phase of life. In the configuration of this age phase, there are discourses, symbols, meanings and practices that are built in the daily action of the most diverse social agents, such as the family, the school, the State and even the media (Netto, Brei, & Flores-Pereira, 2010).

To achieve the goal of retaining future consumers, marketing management invests in actions that value situations with which the child can identify (Landwehr & Hartmann, 2020). In this sense, the most used strategies in the marketing of food to children have emotional appeals, misleading messages/statements, use of music and characters known to children, in addition to conveying happiness and/or security (Omidvar, 2021).

In this way, according to Landwehr and Hartmann (2020), it is more fun to consume a food when that product involves a character that is part of children's lives and is admired by them.

The emotional appeal in the communication of food products is certain, since children are satisfied with the repetition of advertisements they liked, just as they like and ask for the repetition of stories told by their parents. In these advertisements, the strategies seek to use characters that convey values and lifestyles, through the role they play in the story told in the advertisement (Kelly et al., 2019).

In this sense, the task of instruction has been assigned, among other agents, to television, currently one of the main sources of information about new products for children. Factors arising from urbanization, such as the reduction of physical space for outdoor games, intense vehicle traffic, pollution and violence in cities, in addition to the increasingly early use of technological means, favor sedentary activities such as watching television (Fregoneze & Crescitelli, 2009).

The effects of food television advertising on children's buying behavior indicate that children exposed to advertising will choose advertised products in a significant majority of cases, compared to children who are not exposed to such ads. Added to this is the fact that children exposed to advertisements have greater potential to influence family purchases. Purchase requests for specific brands or foods also reflect the frequency of exposure to advertisements (Carpentier et al., 2019).

A study has found that 44% of advertisements aired on television channels during the morning and aimed at children were related to food (Arnas, 2006). Thus, television influences a person's diet so that the more minutes or hours they are exposed to food advertisements, the more likely they are to buy and consume the advertised food (Kelly et al., 2019).

The study aimed to create a segmentation of the child consumer, based on variables related to food advertising on television. For this, the research was developed using the inductive method, which, according to Vergara (2015), aims to generalize common properties of a number of observed cases. Since the object of study encompasses a large group of individuals with the same characteristics (child consumers), the inductive method is presented as the best option for the development of analyses, since it allows conclusions about certain properties from the observation of some cases, contrary to the deductive method.

As for the approach, the research can be classified as quantitative, as it uses mathematical language to present the reason for the problem, that is, it translates into numbers and, consequently, analyzes and classifies the data obtained (Vergara, 2015; Marconi & Lakatos, 2021 ), through the composition of samples for the collection of data that allowed performing calculations on a given problem, and the Agglomerative Cluster Hierarchical Analysis, which allows the creation of specific groups based on numerical analysis of the answers obtained in the questionnaires.

With regard to the objectives, the investigation is pointed out as having a descriptive character, since the purpose is to detail the particularities of a given population or phenomenon (Vergara, 2015). In the case of market segmentation, this detailing was done through the analysis and study of clusters of a specific group of consumers, regarding the influence of television food advertisements on their behavior, through the convergence of particularities observed in their responses to the applied questionnaire.

Aiming at collecting data to fulfill the research objective, data collection was carried out in six schools, chosen for convenience (Creswell & Creswell, 2021), located within a radius of 3 km away from the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), central point of research development, two public and four private.

The objective and methodology of the research were presented to the Directors or Coordinators responsible for the children who study in the school years with predominance of the ages focused on this research, and they were asked, if they agreed, to sign the Term of Authorization for Conducting the Research.

The universe of the research is composed of children aged between seven and twelve years old. The minimum age of the children to answer the questionnaire was chosen based on studies by John (1999), which says that the child is in the socialization stage of consumption, also called the “Analytical Stage”, from the age of seven, developing the cognitive and social ability. At this stage, children are able to understand concepts about brands and advertisements from a perspective that goes beyond their feelings (John, 1999). For the choice of the maximum age, article 2 of Law nº 8.069, of July 13, 1990 (Statute of the Child and Adolescent) was considered, in which a child is considered, “[...] the person up to twelve years of age incomplete” (BRASIL, 1990).

To calculate the sample size, a finite population of 1350 students was considered, corresponding to the total number of children within the age range of 7 to 12 incomplete years, students from the schools selected for the study in the municipality of Campo Grande-MS, being confidence level of 95% and standard error of 6% [Z= 1.96; p=0.5; q=0.5; E=0.06; N = 1350], obtaining a number of 267 (infinite population sample). By applying the correction factor for finite populations, the stipulation of the sample size was 223 individuals (Anderson, Sweeney, & Willians, 2020). However, for greater security, 300 questionnaires were applied, however, of these, 283 were validated, making the standard error 5.8%.

As a data collection tool, a structured questionnaire was used (Malhotra, 2019) consisting of questions about the child's behavior in relation to television media and food advertisement on television, as shown in Chart 1. For such questions, he used The scale based on Gwozdz and Reisch (2011) in a free translation into Portuguese was used as a scale for evaluating statements by children, ranging from “I strongly agree”, “I somewhat agree”, “I somewhat disagree”, and “I strongly disagree”.

Chart 1 - Research variables and questions.

|

Variables |

Questions |

Base authors |

|

Credibility of food advertising on television |

1 - Food advertisements on television offer tasty things that are good for our body. |

Gwozdz e Reisch (2011) |

|

2 - Television advertisements give you the best tips on what foods you should eat and drink. |

||

|

Distrust of food advertising on television |

3 - Eating everything shown in advertisements for food and drinks on television will make you fat. |

|

|

4 - To eat healthy food, you shouldn't eat the things that are shown in television advertisements. |

||

|

5 - Television advertisements convince people to buy foods they should not eat or drink. |

||

|

Television food advertising entertainment |

6 - Advertisements for food and drinks on television are fun and make you laugh. |

|

|

7 - Without advertisements for food and drinks, television would be much more boring. |

||

|

Child's preference for television media |

8 - Of all your free time, how much time do you spend watching television? |

Alves (2011); McNeal (1992) |

|

Aptitude for primary market |

9 - Do you get an allowance or money as a gift? |

McNeal (1998); Veloso; Hildebrand; Campomar (2012) |

|

Evident purchase desire after exposure to television advertisements |

10 - Do you buy or ask someone to buy the food you see on television? |

Suwandinata (2011); Veloso; Hildebrand; Campomar (2012) |

|

Apparent desire to purchase after exposure to television advertisements |

11 - Do you really want to buy a product after seeing it on television? |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

The procedure for data collection took place between May and June of 2019 and involved the use of the survey method, which captures information about the opinions and particularities of a certain group of individuals through questionnaires (Malhotra, 2019). After obtaining authorization from the Directors of the institutions, parents were given the Free and Informed Consent Term (TCLE) to allow or deny their child's participation in the research. Upon obtaining permission, the children were given the Term of Assent and the questionnaire to answer. The research was authorized by the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Beings of the UFMS, under opinion nº 675.195. The questionnaire, which was specifically designed for this age group, was explained and distributed by the researchers who provided assistance and clarified any doubts.

Cluster analysis was used to identify segments of the children's audience based on their behavior in relation to television media and food advertisement on television. This method involves grouping sample elements based on their similarity, thereby reducing internal heterogeneity and arriving at a single segment (Hair et al., 2009; Batistuti, 2012). The identified segments will be used to better understand the behavior of children in relation to food advertising on television.

In order to verify the possible existence of distinct segments among children regarding the influence of food advertising on television, a cluster analysis was performed using the Behavioral Variables. The method chosen was the Ward Method, which starts the analysis with a segment for each respondent, in the case of this research, 283, and clusters the closest groups until forming a single segment, however, in order to always seek the minimal internal variation of the groups (Hair et al., 2009).

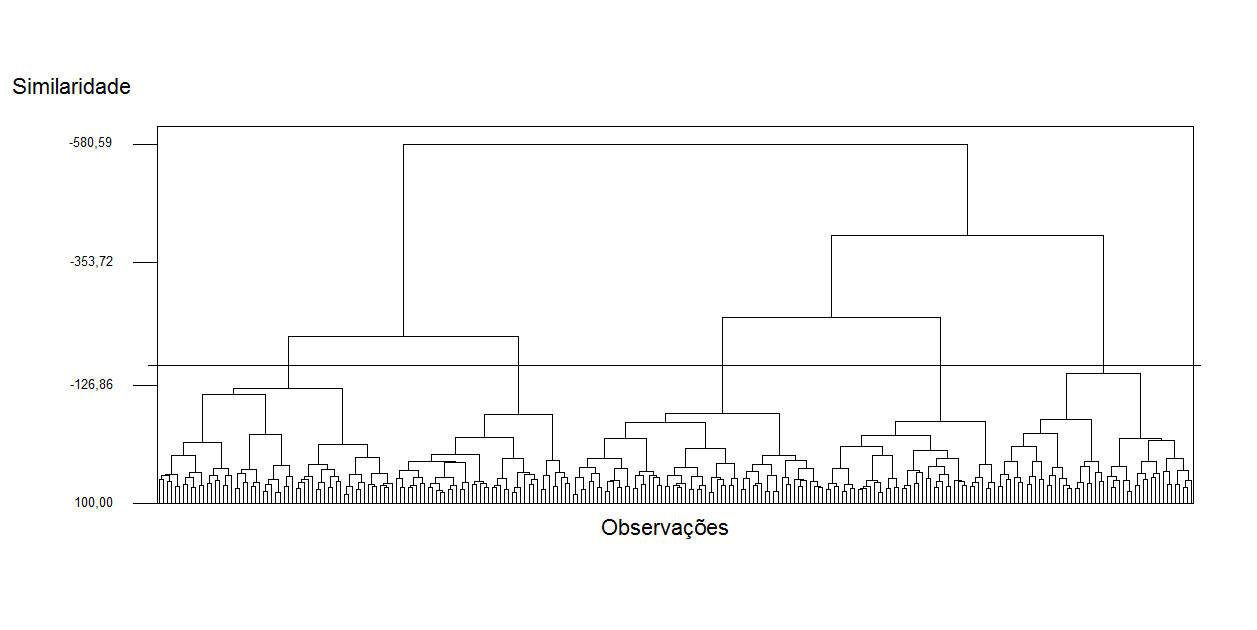

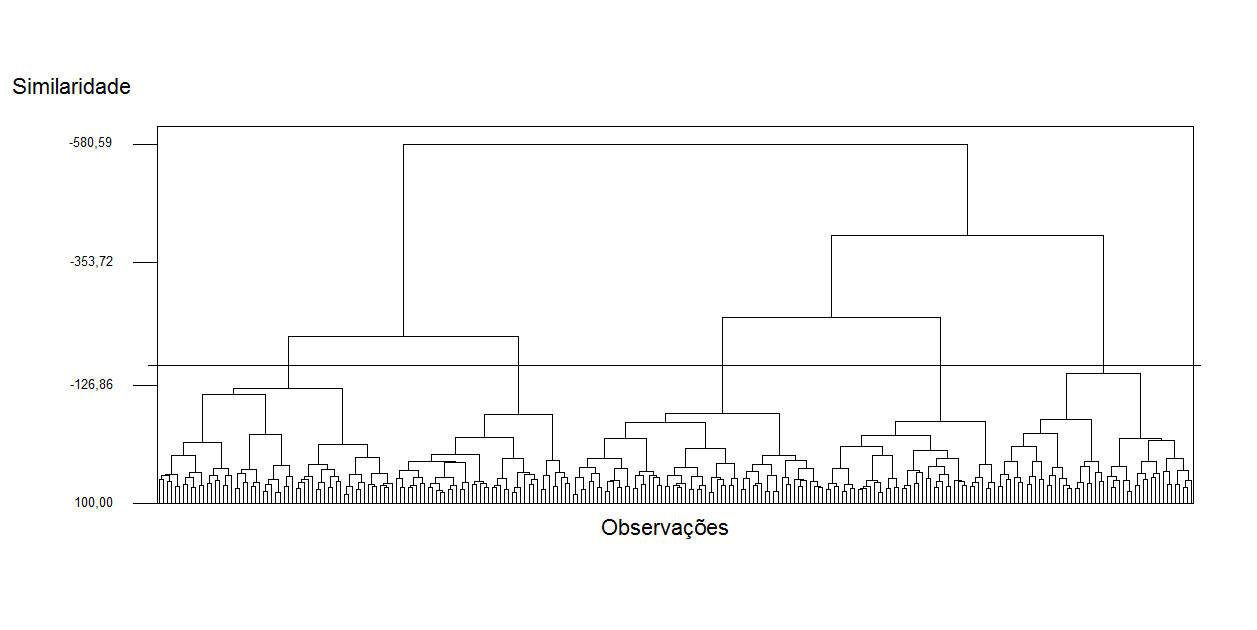

After processing the analysis in the statistical software, the dendrogram was generated to visualize the distribution of the clusters, which showed the formation of five clusters, based on the cut made at the greatest distance between the groups, seeking the greatest possible heterogeneity. between the groups, as can be seen in Figure 1:

Figure 1 – Dendrogram

Similarity

Observations

Fonte: Reseach data (2019)

From the five perceived clusters, a new data processing was carried out, now, fixing the number of clusters in five, so that they could be dimensioned and analyzed. In this way, the distribution of the sample among the clusters was obtained according to Table 1:

Table 1 - Participation of each cluster in the sample

|

Clusters |

% |

|

Cluster1 |

24,42% |

|

Cluster2 |

18,99% |

|

Cluster3 |

22,87% |

|

Cluster4 |

16,67% |

|

Cluster5 |

17,05% |

Source: Research data (2019)

After selecting the number of segments, it was necessary to identify their characteristics, which turns them into groups with a more homogeneous behavior and profile among themselves and more heterogeneous in relation to the other groups. For this, a cross tabulation was performed between the behavioral variables (used for processing the clusters), so that it could be verified which are the characteristics that differentiate them.

Once the cross tabulations were performed between all the variables mentioned above, the next step was to perform a selection of those variables in which there was a greater correlation. For this purpose, the crossings were selected that, by the Chi-square test, presented a p-value ≤ 0.05, thus being able, with 95% reliability, to reject the Ho hypothesis that the variables are independent (Anderson et al., 2020). Given this, Table 2 presents the characterization of each of the clusters in relation to the variables and their response levels:

Table 2 - Variables significantly correlated with each cluster

|

Variables |

Clusters |

P-valor |

|||||

|

Question |

Response levels |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

|

2 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

12,7 |

4,08 |

49,15 |

39,53 |

6,82 |

0 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

22,22 |

28,57 |

28,81 |

44,19 |

25 |

||

|

Somewhat agree (%) |

41,27 |

34,69 |

18,64 |

13,95 |

45,45 |

||

|

Strongly agree (%) |

23,81 |

32,65 |

3,39 |

2,33 |

22,73 |

||

|

3 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

0 |

46,94 |

0 |

2,33 |

2,27 |

0 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

3,17 |

40,82 |

8,47 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Somewhat agree (%) |

22,22 |

2,04 |

30,51 |

32,56 |

13,64 |

||

|

Strongly agree (%) |

74,6 |

10,2 |

61,02 |

65,12 |

84,09 |

||

|

5 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

0 |

24,49 |

18,64 |

6,98 |

0 |

0 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

11,11 |

20,41 |

10,17 |

9,3 |

4,55 |

||

|

Somewhat agree (%) |

44,44 |

26,53 |

23,73 |

44,19 |

31,82 |

||

|

Strongly agree (%) |

44,44 |

28,57 |

47,46 |

39,53 |

63,64 |

||

|

6 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

25,4 |

24,49 |

32,2 |

69,77 |

2,27 |

0 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

26,98 |

20,41 |

27,12 |

20,93 |

11,36 |

||

|

Somewhat agree (%) |

28,57 |

32,65 |

32,2 |

9,3 |

45,45 |

||

|

Strongly agree (%) |

19,05 |

22,45 |

8,47 |

0 |

40,91 |

||

|

7 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

15,87 |

30,61 |

40,68 |

51,16 |

15,91 |

0 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

26,98 |

28,57 |

33,9 |

30,23 |

27,27 |

||

|

Somewhata gree (%) |

28,57 |

16,33 |

22,03 |

18,6 |

36,36 |

||

|

Strongly disagree (%) |

28,57 |

24,49 |

3,39 |

0 |

20,45 |

||

|

11 |

I never feel like buying a product after I see it on TV (%) |

3,17 |

12,24 |

5,08 |

39,53 |

20,45 |

0 |

|

If it's food, yes (%) |

26,98 |

16,33 |

5,08 |

16,28 |

22,73 |

||

|

if it's a toy, yes (%) |

63,49 |

57,14 |

79,66 |

34,88 |

54,55 |

||

|

Yes, if it is another type of product that is not a toy or food (%) |

6,35 |

14,29 |

10,17 |

9,3 |

2,27 |

||

|

9 |

Not (%) |

26,98 |

30,61 |

23,73 |

55,81 |

13,64 |

0 |

|

Yes, I receive allowance (%) |

36,51 |

32,65 |

33,9 |

9,3 |

15,91 |

||

|

Yes, I receive gift money (%) |

36,51 |

36,73 |

42,37 |

34,88 |

70,45 |

||

|

10 |

No, I never buy, nor do I ask them to buy (%) |

7,94 |

28,57 |

30,51 |

55,81 |

27,27 |

0 |

|

Yes, whenever I go to the supermarket with someone (%) |

39,68 |

32,65 |

42,37 |

30,23 |

34,09 |

||

|

Yes, even when I don't go to the supermarket with someone, I ask them to buy what I saw on TV (%) |

42,86 |

34,69 |

25,42 |

9,3 |

36,36 |

||

|

Yes, I buy the food I want with my own money (%) |

9,52 |

4,08 |

1,69 |

4,65 |

2,27 |

||

|

1 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

1,59 |

0 |

13,56 |

11,63 |

9,09 |

0,005 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

23,81 |

18,37 |

37,29 |

25,58 |

22,73 |

||

|

Somewhat agree (%) |

50,79 |

44,9 |

38,98 |

51,16 |

45,45 |

||

|

Strongly agree (%) |

23,81 |

36,73 |

10,17 |

11,63 |

22,73 |

||

|

4 |

Strongly disagree (%) |

4,76 |

18,37 |

13,56 |

6,98 |

0 |

0,013 |

|

Somewhat disagree (%) |

26,98 |

36,73 |

27,12 |

23,26 |

15,91 |

||

|

Somewhat agree (%) |

38,1 |

32,65 |

33,9 |

44,19 |

40,91 |

||

|

Strongly agree (%) |

30,16 |

12,24 |

25,42 |

25,58 |

43,18 |

||

|

8 |

A little bit of my free time (%) |

36,51 |

44,9 |

59,32 |

69,77 |

47,73 |

0,049 |

|

Most of my free time (%) |

49,21 |

40,82 |

32,2 |

20,93 |

34,09 |

||

|

All my free time (%) |

14,29 |

14,29 |

8,47 |

9,3 |

18,18 |

||

Source: Research data (2019)

Chart 2 presents the representative predominance of factors for differentiating and labeling the groups.

Table 2 - Representative predominance of factors for differentiation and labeling

|

Cluster 1 – children moderately influenced by food advertising on television |

Cluster 2 – children little influenced by food advertising on television |

|

⮚ Somewhat agree that television advertisements convince people to buy food they shouldn't eat or drink. ⮚ Strongly agree that without food and beverage advertisements, television would be much more boring. ⮚ Makes you want to buy a product after seeing it on television if it's food ⮚ Earn allowance ⮚ Buys or asks someone to buy the food you see on television even when you don't go to the supermarket with someone ⮚ I buy the food you want with your own money ⮚ Much of his free time is spent watching television

|

⮚ Strongly agree that television advertisements give you the best tips on what foods you should eat and drink. ⮚ Strongly disagree that eating everything shown in food and drink advertisements on television will make you fat. ⮚ Slightly disagree that eating everything shown in food and drink advertisements on television will make you fat. ⮚ Strongly disagrees that television advertisements convince people to buy food they shouldn't eat or drink. ⮚ Slightly disagree that television advertisements convince people to buy food they shouldn't eat or drink. ⮚ Strongly agree that food advertisements on television offer delicious things that are good for the body. ⮚ Strongly disagrees that in order to eat healthy foods, you shouldn't eat the things that are advertised on television. ⮚ Makes you want to buy a product after seeing it on television if it is a product other than a toy or food ⮚ Slightly disagree that in order to eat healthy food, you shouldn't eat the things shown in television advertisements. |

|

Cluster 3 – children not resistant to the influence of food advertising on television |

Cluster 4 – children not influenced by food advertising on television |

|

⮚ Strongly disagree that television advertisements give you the best tips on what foods you should eat and drink. ⮚ Slightly disagree that advertisements for food and drinks on television are fun and laughable. ⮚ Slightly disagree that without food and drink advertisements, television would be much more boring. ⮚ Makes you want to buy a product after seeing it on television if it's a toy yes ⮚ Buys or asks someone to buy the food you see on television whenever you go to the supermarket with someone ⮚ Strongly disagree that food advertisements on television offer delicious things that are good for the body. ⮚ Slightly disagree that food advertisements on television offer tasty things that are good for our body. |

⮚ Slightly disagree that television advertisements give the best tips on what foods you should be eating and drinking. ⮚ Do you agree that eating everything shown in food and drink advertisements on television will make you fat? ⮚ Strongly disagrees that advertisements for food and drinks on television are fun and laughable. ⮚ Strongly disagree that without food and beverage advertisements, television would be much more boring. ⮚ Never feel like buying a product after seeing it on TV ⮚ No allowance or gift money ⮚ No, I never buy, nor do I ask them to buy ⮚ Do you agree that food advertisements on television offer tasty things that are good for the body? ⮚ Do you agree that in order to eat healthy food, you shouldn't eat the things shown in television advertisements. ⮚ Some free time is spent watching television |

|

Cluster 5 – children very influenced by food advertisement on television |

|

|

⮚ Somewhat agree that television advertisements give the best tips on what foods you should eat and drink. ⮚ Do you agree that eating everything shown in food and drink advertisements on television will make you fat? ⮚ Strongly agree that television advertisements convince people to buy food they shouldn't eat or drink. ⮚ Somewhat agree that advertisements for food and drinks on television are fun and laughable. ⮚ Strongly agree that advertisements for food and drinks on television are fun and laughable. ⮚ Do you agree that without food and beverage advertisements, television would be much more boring. ⮚ Earn gift money ⮚ Strongly agree that in order to eat healthy food, you shouldn't eat the things shown in television advertisements. ⮚ All free time is spent watching television |

|

Fonte: Dados da pesquisa (2019)

Cluster 1 – children moderately influenced by food advertising on television

It corresponds to 24.42% of the sample and children are the ones who are influenced by advertising at a moderate level, as they somewhat agree that television advertisements convince people to buy foods that they should not eat or drink.

Children buy the food they want with their own money, in addition to asking to buy it even when they do not go to the supermarket, which shows that, in this cluster, in addition to being part of the future market (children as adults consumers of products they have known since childhood), make up the primary market (when they buy, themselves, with their own money) and the influencer market (when they directly request the purchase of something or when it occurs indirectly, as someone, knowing the child's preferences, buys something that fits these preferences) (McNeal, 2000; Kaur & Singh, 2006).

The children in this cluster strongly agree that without advertisements for food and drinks, television would be much more boring, and they are very eager to buy a product after seeing it on television if it is food. These points are corroborated by the fact that advertisements for food intended for children present emotional appeals, as exposed by Omidvar (2021), in which advertisements seek to convey happiness and, according to Solomon (2016), there is the expectation of children that the advertising amuse them, make them laugh.

Another characteristic of this cluster is that the children receive an allowance and a significant part of their free time is spent watching television. This may explain why they are part of the primary market (McNeal, 2000; Kaur & Singh, 2006) and why they tend to ask for specific brands or foods even when they are not going to the supermarket. This reflects their frequency of exposure to advertisements (Carpentier et al., 2019).

Cluster 2 – children little influenced by food advertising on television

It corresponds to 18.99% of the sample and it is the children who most strongly agree that advertisements on television give the best tips on what foods you should eat and drink; those who disagree a lot and a little bit that eating everything shown in food and drink advertisements on television will make you fat; those who most disagree a lot and a little that television advertisements convince people to buy food they shouldn't eat or drink; those who most agree that food advertisements on television offer tasty things that are good for the body; those who disagree a lot and a little bit that in order to eat healthy food, they shouldn't eat the things shown in television advertisements.

These data, from the point of view of children's collective health, can be worrying, as television advertisements present emotional appeals, deceptive information (Omidvar, 2021) and that children exposed to advertisements choose, at rates significantly higher than children who are not exposed, the products advertised in them (Carpentier et al., 2019), an aggravating factor being the fact that most food advertisements on television feature foods high in fat and sugar (Arnas, 2006) .

However, the children in this cluster are the ones who are most eager to buy a product after seeing it on television if it is another type of product that is not a toy or food. That is, they are influenced and demonstrate to believe/trust in television advertisements, but they point out that they do not feel like consuming the foods or toys seen in them, but the other advertised products.

Cluster 3 – children not resistant to the influence of food advertising on television

It corresponds to 22.87% of the sample and it is the children who most strongly disagree that advertisements on television give you the best tips on what foods you should eat and drink; those who disagree a little bit that food and beverage advertisements on television are fun and make people laugh; those who disagree a little bit that without food and drink advertisements, television would be much more boring; those who most disagree a lot and a little that food advertisements on television offer delicious things that are good for the body; they are very willing to buy a product after seeing it on television if it is a toy, which shows that these children are more vulnerable to toy advertisements.

However, the children in this cluster are the ones who buy or ask someone to buy the food they see on television whenever they go to the supermarket with someone, which, according to Carpentier et al. (2019), is linked to the frequency of exposure to advertisements and, the more exposure, the more likely they are to buy and consume the advertised food (Kelly et al., 2019). In this way, it is seen that although they do not show significant agreement with the statements about the influence of food advertisements on television, they are influenced by them by acting as a primary market (buying with their own resources) and influencer (in a direct way, prompting someone to buy the intended product) (McNeal, 2000; Kaur & Singh, 2006) after exposure to them.

Cluster 4 – children not influenced by food advertising on television

It corresponds to 16.67% of the sample, being the smallest group among the 5 obtained. It is the children who most disagree that television advertisements give the best tips on what foods they should eat and drink; those who most agree that eating everything shown in food and drink advertisements on television will make you fat; those who strongly disagree that food and beverage advertisements on television are fun and make people laugh; those who strongly disagree that without advertisements for food and drinks, television would be much more boring.

In this cluster, children are characterized for the most part by never wanting to buy a product after seeing it on TV and they do not earn allowances or money as gifts. Furthermore, they never buy or ask to buy food after seeing it on TV.

These children somewhat agree that food advertisements on television offer delicious things that are good for the body and somewhat agree that in order to eat healthy food, they should not eat the things shown in television advertisements.

In addition, it is important to point out that the public in this cluster are those who most claimed to watch television in just a little of their free time, which again corroborates the correlation presented by Carpentier, Correa, Reyes and Taillie (2019) that children children exposed to advertising will choose and order purchases at a higher rate than less exposed children, which is the case with the public in this cluster.

Cluster 5 – children very influenced by food advertisement on television

It corresponds to 17.05% and it is the children who most agree that television advertisements give the best tips on what foods they should eat and drink. They strongly agree that eating everything shown in food and beverage advertisements on television will make you fat and they shouldn't eat the stuff they see in television advertisements.

These children somewhat agree that food and beverage advertisements on television are fun and laughable and that without food and beverage advertisements, television would be much more boring. And they are also the ones who most strongly agree that food and beverage advertisements on television are fun and make people laugh. This finding corroborates previous studies by Solomon (2016) and Omidvar (2021), which suggest that one of the most common strategies in food advertising is to use emotional appeals aimed at elements of fun to influence children's taste preferences.

In addition, children in this group are the ones who earn the most money as gifts, which allows them to transform the influence of food advertising into direct purchases in the primary market (McNeal, 1992; Kaur & Singh, 2006).

Another important characteristic is that the public in this cluster are those who most stated that they spend all their free time watching television, which corroborates Carpentier, Correa, Reyes and Taillie (2019) regarding the relationship between the level of exposure to advertising and the choice of advertised products and Kelly et al. (2019) as the authors point out that the more minutes or hours a person is exposed to food advertisements, the more likely they are to buy and consume the advertised food.

The construction of the five clusters, delimited through the dendrogram analysis, presented a detailed division on the impact of television advertising on children's consumers, demonstrating that the influence of such marketing tools are diverse, as can be seen through the names of the clusters, which indicate the variation among children who are little, moderately, or very influenced by television media. This highlighted differentiation contributes to a better understanding of consumer behavior.

The child consumer gained the attention of researchers and marketing professionals as they became a primary market agent and an influencer in family purchases. To reach this child consumer, various media are used, but among them television, communicating products with advertisements capable of attracting the child's attention. Of the products advertised on television commercials, there is the food category, which are part of the child's buying behavior processes from the first years of life. Thus, the overall objective was to segment the child consumer based on variables related to food advertising on television.

It was possible to note the existence of segmentation in the children's market based on variables related to food advertising on television. The 5 segments are: “children very influenced by food advertisements on television”, “children moderately influenced by food advertisements on television”, “children little influenced by food advertisements on television”, “children not resistant to the influence of food advertisements on television”. food on television” and “children not influenced by food advertising on television”.

This research contributes to the academic and corporate universe as it presents new data on the segmentation of the consumer market (children), such as the perception of this public about the impact of television advertisements and the level of influence that such marketing tools have on a group specific consumers, generating important information for decision-making by managers, with regard to marketing strategies and the composition of advertisements and advertisements that are effective in engaging this public in question, since their behavior becomes clearer and more predictable from the presentation of new conclusions, such as those presented in this study.

The main limitation of the study is the sample, stipulated for convenience, of six schools, in the city of Campo Grande/MS, which limits the statistical inferences about the behavior of child consumers, in the national territory; in addition, the response scales of the questionnaire questions had to be simplified in an adaptation so that the children could understand them, which can restrict the amount of information collected in each question.

As a direction for future research, it is suggested to carry out studies with larger and probabilistic samples; use questionnaires with more complex response scales; to study the influence of food advertisements broadcast on media other than television; the influence of the language used and/or manipulated in advertisements aimed at children and semiotic elements, and researching the existence of new segments in the children's market with the psychosocial changes that occur over time.

Alves, M. A. (2011). Marketing infantil: um estudo sobre a influência da publicidade televisiva nas crianças (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal.

Anderson, D. R., Sweeney, D. J., & Williams, T. A. (2020). Estatística aplicada à administração e economia (5ª ed.). Cengage Learning Brasil.

Arnas, Y. A. (2006). The effects of television food advertisement on children’s food purchasing requests. Pediatrics International, 48, 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02180.x

Batistuti, M. R. (2012). Classificação de fungos através da espectroscopia no infravermelho por transformada de Fourier (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo. https://doi.org/10.11606/D.59.2012.tde-31012013-094052

Brasil. (1990). Lei nº 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. Diário Oficial da União, 16 de julho de 1990, Seção 1, p. 18551.

Bonoma, T., & Shapiro, B. P. (1983). Industrial market segmentation: a nested approach. https://www.msi.org/reports/industrial-market-segmentation-a-nested-approach/

Carpentier, F. R. D., Correa, T., Reyes, M., & Taillie, L. S. (2020). Evaluating the impact of Chile’s marketing regulation of unhealthy foods and beverages: Preschool and adolescent children’s changes in exposure to food advertising on television. Public Health Nutrition, 23(4), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019003355

Chaudhary, M., & Gupta, A. (2012). Exploring the influence strategies used by children: An empirical study in India. Management Research Review, 35(2), 1153–1169. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171211281273

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2021). Projeto de pesquisa: métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto (5ª ed.). Penso.

Fregoneze, G. B., & Crescitelli, E. (2009). Os efeitos da propaganda no comportamento de compra do público infantil. Revista Administração e Diálogo, 12(1), 122–148.

Gbadamosi, A. (2017). Young consumer behaviour: A research companion. Taylor & Francis.

Gross, G. (2010). Children and the market: An American historical perspective. In D. Marshall (Ed.), Understanding children as consumers. Sage.

Gwozdz, W., & Reisch, L. A. (2011). Instruments for analysing the influence of advertising on children’s food choices. International Journal of Obesity, 35(Suppl 1), S137–S143.

Hair, J. H., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados (6ª ed.). Bookman.

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183–213. https://doi.org/10.1086/209559

Kaur, P., & Singh, R. (2006). Children in family purchase decision-making in India and the West: A review. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 8(1), 1–30.

Kelly, B., Boyland, E., King, L., Bauman, A., Chapman, K., & Hughes, C. (2019). Children’s exposure to television food advertising contributes to strong brand attachments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 2358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132358

Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2019). Administração de marketing (15ª ed.). Pearson.

Landwehr, S. C., & Hartmann, M. (2020). Industry self-regulation of food advertisement to children: Compliance versus effectiveness of the EU Pledge. Food Policy, 91, 101833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101833

Lucchese, T., Batalha, M. O., & Lambert, J. L. (2006). Marketing de alimentos e o comportamento de consumo: Proposição de uma tipologia do consumidor de produtos light e/ou diet. Organizações Rurais & Agroindustriais, 8(2), 227–239.

Malhotra, N. K. (2019). Pesquisa de marketing: uma orientação aplicada. Bookman.

Marconi, M. A., & Lakatos, E. M. (2021). Fundamentos de metodologia científica (9ª ed.). Atlas.

McNeal, J. U. (1992). Kids as customers: A handbook of marketing to children. Lexington Books.

McNeal, J. U. (1998). Tapping the three kids' markets. American Demographics, 20(4), 6–36.

McNeal, J. U. (2002). Children as consumers of commercial and social products. Pan American Health Organization.

Mirapalheta, R. F. (2005). Os estilos parentais e a influência relativa dos adolescentes nas decisões de consumo familiar (Tese de Doutorado). Fundação Getúlio Vargas, São Paulo.

Norman, J., Kelly, B., McMahon, A., Boyland, E., Baur, L. A., Chapman, K., King, L., Hughes, C., & Bauman, A. (2018). Children's self-regulation of eating provides no defense against television and online food marketing. Appetite, 125, 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.026

Omidvar, N., Al-Jawaldeh, A., Amini, M., Babashahi, M., Abdollahi, Z., & Ranjbar, M. (2021). Food marketing to children in Iran: Regulation that needs further regulation. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science, 9(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.9.3.02

Netto, C. F. S., Brei, V. A., & Flores-Pereira, M. T. (2010). O fim da infância? As ações de marketing e a “adultização” do consumidor infantil. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 11(5), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-69712010000500007

Palmer, R. A., & Millier, P. (2004). Segmentation: Identification, intuition, and implementation. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(8), 779–785.

Santos, S. L., & Batalha, M. O. (2010). Propaganda de alimentos na televisão: Uma ameaça à saúde do consumidor? Revista de Administração, 45(4), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0080-2107(16)30468-X

Smith, R., Kelly, B., Yeatman, H., & Boyland, E. (2019). Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: A systematic critical review. Nutrients, 11, 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040875

Solomon, M. R. (2016). O comportamento do consumidor: comprando, possuindo e sendo (11ª ed.). Bookman.

Souza, A. R. L., & Révillion, J. P. P. (2012). Novas estratégias de posicionamento na fidelização do consumidor infantil de alimentos processados. Ciência Rural, 42(3), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782012000300030

Suwandinata, H. (2011). Children’s influence on the family decision-making process in food buying and consumption (Tese de Doutorado). Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Alemanha.

Tonks, D. G. (2009). Validity and the design of market segments. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(3–4), 341–356.

Veloso, A. R., Hildebrand, D. F. N., & Daré, P. R. C. (2008). A criança no varejo de baixa renda. RAE eletrônica, 7(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-56482008000200003

Veloso, A. R., Hildebrand, D., & Campomar, M. C. (2012). Marketing e o mercado infantil. Cengage Learning.

Vergara, S. C. (2015). Métodos de pesquisa em administração (6ª ed.). Atlas.

Vivarta, V. (2009). Infância e consumo: Estudos no campo da comunicação. ANDI Instituto Alana.