Mário César Sousa de Oliveira[i], Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3605-7896; Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFCA) – Juazeiro do Norte – Ceará, Brasil. E-mail: mario.sousa@ufca.edu

Michel Melo Arnaud[ii], Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2875-8676; Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará (UNIFESSPA) – Rondon do Pará – Pará, Brasil. E-mail: michel@unifesspa.edu.br

Lucas Bastos Brito[iii], Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2292-2554; Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará (UNIFESSPA) – Rondon do Pará – Pará, Brasil. E-mail: lucasbastos@unifesspa.edu.br

Lorena Madruga Monteiro[iv], Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3720-7684; Centro Universitário de Maceió (UNIMA/Afya) – Maceió – Alagoas, Brasil. E-mail: lorena.madruga@gmail.com

Abstract

The present study aims to measure the technical efficiency of the municipalities from the Southeast mesoregion of the state of Pará in the use of resources to provide health services. The research identified disparities between the found levels of efficiency, taking as reference the municipalities from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará. The method used to measure efficiency was the data envelopment analysis. As a result of the study, it was noticed the discrepancy between the degree of technical efficiency among the municipalities, and of the 30 cities that made up the sample, 15 showed an excellent degree of efficiency, 10 a good degree of efficiency and 5 a weak degree of efficiency. The study points out the need to create an institutional relationship network where managers can seek alternatives to exchange successful experiences in municipalities close to their context.

Keywords: management; public expenditure; decisions.

Resumo:

O presente trabalho tem como objetivo mensurar a eficiência técnica dos municípios da região sudeste do estado do Pará na utilização dos recursos para prover serviços em saúde. A pesquisa identificou disparidades entre os níveis de eficiência encontrados, tomando como referência os municípios da mesorregião sudeste paraense. O método utilizado foi para medir a eficiência foi a Análise Envoltória de Dados. Como resultados do estudo foi perceptível a discrepância entre o grau de eficiência técnica entre os municípios, sendo que dos 30 municípios que compunham a amostra do estudo, 15 apresentaram um grau de eficiência excelente, 10 municípios obtiveram um grau de eficiência classificado como bom e 5 dos municípios da amostra obtiveram um fraco grau de eficiência. O estudo aponta a necessidade de criação de uma rede institucional de relacionamento onde os gestores possam buscar alternativas de troca de experiências bem sucedidas em municípios próximos ao seu contexto.

Palavras-chaves: gestão. gasto público. decisões

Citation: Oliveira, M. C. S., Arnaud, M. M., Brito, L. B., & Monteiro, L, M. (2025). Technical efficiency and health services: a data envelopment analysis of municipalities from the mesoregion of Southeast Para. Gestão & Regionalidade, v. 41, e20258573. https//doi.org/10.13037/gr.vol41.e2025573

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the search for better management of health services fostered several debates and proposals, however, it was the Federal Constitution of 1988 that brought hope to Brazilian population that their demands and health needs would be guaranteed and supported by the Brazilian State, with the regulation of the Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS (Unified Health System) in 1990. The universality and comprehensiveness of care, a decentralization of decision-making power and efficiency in the quality of services provided are the principles that guided its implementation and currently guide its operation.

Opportunately, according to Rodrigues, Gontijo and Gonçalves (2021 ), access to health, now universal, starts to play a relevant role in the process of development and well-being of citizens. Inserted in this context, a framework of imperative questions emerges, especially for managers of public resources, such as management, inspection and monitoring of services provided (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009; Machado et al., 2019; Medeiros & Marcolino, 2018).

However, it was noticed over time that maintaining a public health system was very complex, given the growing demand, the lack of infrastructure, the lack of human resources and, mainly, the lack of financial resources (Medeiros; Marcolino, 2018). The issues involving public health management are diverse, making it necessary to rationalize health actions, analyzing their cost-effectiveness and minimizing mistakes in directing investments and conducting public policies, always seeking to optimize the use of resources (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009).

For there to be a maximization of health services, it is essential that knowledge and technologies are in agreement with ethical principles and consider the restrictions given by human and financial resources. Health services must be macroeconomically efficient, aiming at cost control, and microeconomically, focusing on maximizing the service offered and user satisfaction and minimizing costs (Viacava et al., 2012).

With the creation of SUS, the federal government decentralized health services, transferring most of the responsibility to the states and cities, by transferring financial resources to states and cities funds and, hence, the provision of health services, administration and quality assurance of health services under the responsibility of the states and cities managers. The Decentralization was necessary, since Brazil has a territory of continental dimensions, with enormous regional differences and composed mostly of small municipalities (Viacava et al., 2012).

In parallel with the challenges faced by city managers, there are frequent questions and complaints published in newspapers and other types of media about the quality of the services offered by SUS. Therefore, it becomes increasingly necessary to use methods and techniques that allow evaluating the efficiency of actions in public policies and the supply of public health services considering the available resources.

There is a need to assess health services in full, however, health assessment has used partial indicators, even though they are still important for management, but provide a fractional assessment of the system. Corroborating this assertion, Rodrigues, Gontijo and Gonçalves (2021) expose that evaluation of health services is interesting to public managers, users and inspection control bodies, aiming at the primacy for the quality of services and better management of the applied resources (Cesconetto, Lapa, & Calvo, 2008).

The assessment of a given health system has been recurrent in the literature. Schneider et al. (2017) assessed the performance of the health care system from United States of America and compared it to Canada and 11 other European countries, ranking it last in terms of equity and affordability. Sun et al. (2017) presented a longitudinal study that aims to examine the efficiency of national health systems in 173 countries from 2004 to 2011 by using the data envelopment analysis (DEA methodology). Complementarily, Massuda et al. (2018) presented a study about the health system in Brazil from 2003 to 2014, , whose results highlighted structural problems of the system as well as a budgetary governance system in need of adjustments.

Opportunely, seeking to contribute to this debate, the present study aims to measure the technical efficiency of the municipalities from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará in the use of resources to provide health services. To achieve the proposed objective, the study seeks to answer the following research question: what is the degree of efficiency of the municipalities of Southeast Pará in the use of resources to provide services in the health area?

The development of this work is justified , primarily, by the scarce literature with this theme developed in a regionalized way, mainly in the mesoregion of Southeast Pará, but also by the current sociopolitical scenario, composed of the increased demand for public health services driven by several factors, such as: higher life expectancy, lifestyle, rising unemployment and a strong tendency to reduce transfers of financial resources from the nation to the municipalities, which should impact the services offered to the population.

Certainly, the resources allocated to public health have suffered drastic reductions in the latest years, contributing to the resurgence of regional inequalities (Massuda et al., 2018). Ratifying this scenario, Soares Filho et al. (2020) states that in the state of Pará, primary health care has shown harmful effects due to the reduction in resources, since there is an urgent need to monitor health resources and services provided in public health, which can contribute to the spatial and geographic analysis of health public resources.

The research focused on the municipalities located in the mesoregion of Southeast Pará. The initial sample of the research is composed of 39 cities from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará and among them municipalities that are of great importance for the region, such as Marabá, Paragominas and Parauapebas.

The study is structured in six topics, considering the introduction and the final considerations. The second topic represents the theoretical foundation, and the third one describes the method used, the fourth one presents the data used and the fifth shows the analysis of the obtained results.

Morais (2009, p. 3) defines efficiency as the ability “to obtain a certain effect, strength, effectiveness, [...]has the meaning of action, strength, virtue of producing an effect, effectiveness. The word effectiveness, on the other hand, designates that thing which produces the desired effect”. Within the scope of Public Administration, efficiency is one of the constitutional principles that govern the actions of public managers. However, the new model of Public Administration (managerialist) that emerged from the 1990s in Brazil focuses on the customer-citizen, on control and transparency in Public Administration has the main guiding principle of efficiency.

The principle of efficiency was introduced in the Federal Constitution of 1988 through the Constitutional Amendment number 19 of 1998, which guides public managers to find solutions to the problems of municipalities through better management practices, meeting the various public demands (ROSA, 2018). The principle of efficiency directs public managers to find solutions to the challenges and problems that affect the municipalities through the best management practices, meeting public demands considering the aforementioned values (Morais, 2009).

In order to achieve the expected efficiency in the public sector, it is necessary to invest in the improvement of its managers and public agents, so that their functions are carried out with greater professionalism. The new public management requires public managers to be prepared and searching new knowledge so that they are able to efficiently apply the resources collected by the municipalities, together with the citizens, thus providing a better quality of life for all (ROSA, 2018).

The Constitutional Amendment number 19 of 1998 added the § 7º in the Article 39 of the Federal Constitution of 1988, claiming that:

§ 7º Law of the Union, states, of the Federal District and municipalities will regulate the application of budget resources from the economy with current expenses in each body, autarchy and foundation, for the application in the development of quality and productivity programs, training and development, modernization, reequipping and rationalization of the public service, including in the form of additional or productivity bonus (Brasil, 1988, 1998).

The search for efficiency can generate changes in the functional behavior of the Administration, with a focus on the social interest, in order to guarantee human dignity.

The SUS was created to guarantee the universal right to health, as provided in the article 196 of the Federal Constitution of 1988, with the organizational arrangement guided by the principles and guidelines defined in the article 7 from the Law number 8080 of 1990 and, through concrete actions ,support health policy in Brazil (Brasil, 1988, 1990). The guiding principles of SUS are universality, integrality and equality, addition to its guidelines attributing political and administrative autonomy to each sphere of government, whether federal, state or municipal, with an emphasis on decentralization, hierarchization and regionalization of public health services.

However, for various economic and political reasons, the SUS has not yet been implemented in its entirety, even though several studies demonstrate that its principles and guidelines are the way to improve the health system in Brazil (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009). Considering the principles and guidelines of SUS, health efficiency should be thought as the relationship between the cost and the impact of services on the health of the population, maintaining a certain level of quality (Viacava et al., 2012).

Implementing efficient management practices become necessary, since the socio-political reality in Brazil does not allow public managers, mainly municipal, to envision an increase in expenses for the public health sector. It is imperative to implement tools and methodologies that assess the use of available resources in order to maximize the results of services provided both in more advanced regions and in locations that lack adequate infrastructure (Medeiros & Marcolino, 2018).

From the perspective of microeconomics, efficiency is linked to production factors and production costs. The production possibilities frontier considers the maximum production quantities in view of the production factors and available technology in a given period and in a given context. In this sense, economic efficiency presents itself as a productivity indicator, which measures the quantity of products produced in relation to available production factors (Krugman & Wells, 2007)

Health, as a public good, should not be measured, in theory, from the perspective of the frontier of production possibilities. A public good is defined as being non-rival and non-excludable, that is, the access and use by an individual or group of individuals does not reduce its offer to others, just as, regardless of the consumption, it will always be available, not being exclusive of a group or individual (Krugman & Wells, 2007). Specifically, health is considered a meritorious good, of great importance for citizens, and the country guarantees its equity by offering access to all, as in the case of the SUS.

However, as its resources depend on government transfers which compete with other areas, such as education and social assistance, the issue of efficient allocation of resources becomes central. According to Barros (2013, p. 31) “it has been usual to carry out international comparisons of health expenditures and health systems as a way of assessing the performance of different systems and different countries”. According to the author, in general, these surveys aim to compare per capita expenditure in countries with similar levels of development, highlighting the importance of the public sector in these countries represented by the constant need to rationalize health expenditure, since most countries are in a situation of budget deficit (Barros, 2013).

Regarding technical efficiency, in the sense of productivity of human resources, as a doctor does not serve as many people as in the past, due to the advancement of care and preventive medicine, among other factors, the price of health goods and services rises, increasing their importance in the public budget and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of countries (Barros, 2013). However, Barros (2013, p. 40) points out that, according to studies in the area, the trend is not one of great increase, because half of the expenses are due “to the evolution of technological progress, with the appearance of new therapies and technologies, that are more expensive than the previous generation”.

Giraldes (1995, p. 167) understands efficiency as a fundamental principle of the distribution of resources in health systems, and defines it as “the maximization of results for prefixed resources”, in other words, it is about the used resources and the obtained results.

The application of this definition to the health sector is direct; in it we find limited productive resources, generally scarce, and parts of a centralized decision-making process of a political nature. The use of these resources has no prior allocation, and it is up to planners to determine their alternative use. Attributed to the health sector, they result in goods and services that will be distributed according to the characteristics and structure of the health system, with immediate or future impact, reaching individuals or defined groups of the population. Finally, the economic analysis evaluates costs and benefits, taken broadly, for the improvement of distribution forms and future programming of intervention in the sector. (Nero, 1995, p. 20).

Andrade, E. et al. (2007), in a study that evaluates research and production in health economics in Brazil, highlights the importance, both in terms of supply and demand, of the relationship between SUS technical efficiency in the provision of health services. Based on the conclusions of studies in the area, they point out the important dimensions of this relationship: (a) the determination of health management priorities; (b) provides subsidies to formulate allocative decisions in the face of scarce resources; and (c) allows the reflection and action regarding the regulation of services, especially with the incorporation of new technologies.

The management and allocation of health resources in Brazil focus on its federative organization. In this sense, the municipal sphere becomes crucial to understand and test the technical effectiveness and the health services offered, since, after the Federal Constitution of 1988, with the Norma Operacional Básica - NOB (Basic Operational Norm) 01/93, SUS was decentralized, government transfers fall on municipal funds and it is up to municipal managers to manage them (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009).

It can be said that the decentralization process imposed the municipalization in a radical way, where the municipalities start to assume the functions of coordination and management of the local health policy, having to fulfill the goals of the national programs, using the resources destined by the Federal Government. Constitutional Amendment nº29 obliged the Union to invest in health, in 2000, 5% more than it had invested in the previous year and determined that in the following years this value would be corrected by the nominal variation of the GDP. The states were obliged to apply 12% of the tax collection, and the municipalities, 15%. (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009, p. 203).

Given this context, the study of technical efficiency and the provision of health services makes it possible to verify the optimization of resources allocation and to perceive the absence or not of waste on the part of municipal management. In this sense, since it involves the public treasury, “efficiency should be seen as the combination of economic rationality with the values of freedom, equality, justice and defense of well-being” (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009, p. 204).

Data envelopment analysis (DEA) is a non-parametric technique for analyzing performance and efficiency in the public sector. It originates from the model developed by Charnes, Cooper e Rhodes (1978), improved by Banker , Chang e Cooper (1996). However, the two models have different objectives, since,

Initially, the model proposed by Charnes et al. (1978), called CRR, was designed for a scale constant return analysis (CRS – Constant Returns to Scale). It was later extended by Banker, Charles and Cooper (1984, pp. 1078-1092) to include scale-variable reforms (VRS – Variable Returns to Scale) and came to be called BCC. Thus, the basic models of DEA are known as CCR (or CRS) and BCC (or VRS). Each of these two can be designed in two ways to maximize efficiency: 1. Reduce the consumption of inputs, maintaining the level of production, that is, input-oriented. 2. Increase the production, given the levels of inputs, that is, product-oriented (Peña, 2008, p. 92).

It is a methodology for the “comparative measurement of the efficiency of decision-making units (DMUs)” (Lins et al., 2007, p. 886 ), “developed to evaluate the efficiency of organizations whose activities are not aimed at profit or for which there are no fixed prices for all inputs or all products” (Casado, 2007, p. 60). Thus,

The DEA method has been successfully applied to study the efficiency of Public Administration and non-profit organizations. It has been used to compare educational departments (schools, colleges, universities and research institutes), health establishments (hospitals, clinics), prisons, agricultural production, financial institutions, countries, armed forces, sports, transport (road maintenance, airports ), restaurant chains, franchises, courts of law, cultural institutions (theatre companies, symphony orchestras), among others .(Peña, 2008, p. 92)

According to Peña (2008, page 85), “the continuous search for efficiency becomes a prerequisite for the survival of organizations” and, therefore, the use of DEA for measuring efficiency in the public and private sector is justified, since “efficiency is the ability to do things right, to minimize the input-output relationship.” The basic idea is that one should use the same inputs to verify the production of the same outputs. Outputs and inputs can be continuous, ordinary or categorical variables, and can be measured in different units, metrics, etc., as long as the selected units are homogeneous, that is, they produce the same products and services with the same inputs. That is, “ the objective of DEA is to compare a certain number of DMUs that perform similar tasks and they differ in the amounts of input that coexist and outputs that they produce” (Mello et al., 2003, p. 327).

The Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) seeks to measure the relative efficiency of a set of Decision Making Units (DMUs), with regard to an efficient frontier. DEA is a non-parametric method, that is it does not make any assumptions regarding the functional form that the data should take, instead, uses the data itself as a basis, an efficiency frontier is drawn and each DMU will be compared to this frontier, generating an efficiency score (Medeiros & Marcolino, 2018).

DEA was conceived to be applied where products cannot be compared in monetary terms and when it is necessary to reconcile several variables, of a qualitatively and quantitatively different magnitude, in different realities without a pre-established standard. Unlike traditional parametric approaches, DEA optimizes each individual observation in order to determine an efficient linear frontier, which is composed of efficient units and has no input or output slack. The measure of inefficiency can be calculated from the distance of a productive unit (DMU) and that is found below the production frontier found (Cesconetto, Lapa, & Calvo, 2008; Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009).

There are several models of DEA modeling, however, there are two classic models widely used to determine the efficiency frontier: CCR and BCC. The model to be adopted in the present study was the BCC with Variable Returns to Scale (VRS) with orientation to maximize the products (outputs), because ,according to Cesconetto, Lapa e Calvo (2008) and Politelo et al. (2012 apud Medeiros & Marcolino, 2018), the model to be adopted in this study allows a richer analysis of the data, providing a projection of each inefficient DMU over the boundary surface found by efficient DMUs of compatible size.

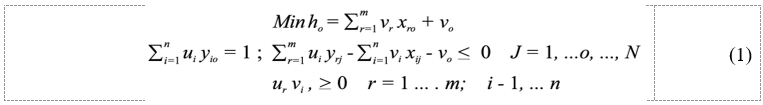

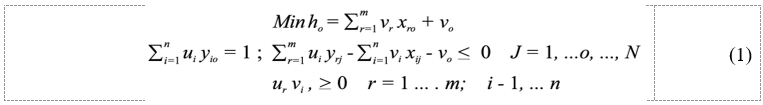

It is considered the most appropriate model, since it distinguishes between technical and scale inefficiencies, estimating pure technical efficiency, with a focus on products. The model in question can be demonstrated as follows (Peña, 2008):

The data submitted to the DEA were extracted from the Departamento de Informática do SUS – DATASUS (SUS IT Department). The databases used in the present study were the Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde – CNES (National Register of Health Establishments), Sistema de Informação Hospitalar - SIAH (Hospital Information System), Sistema de Informação Ambulatorial – SIA (Outpatient Information System) and the Sistema de Informação da Atenção Básica – SIAB (Information from Primary Care), and has 2015 as reference year, (Brasil, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c, 2015d).The choice of the year 2015 as a reference year for the analysis is justified by the lack of data in subsequent years and, for the application of the chosen method, it is necessary that all variables are available, since that incomplete data can provide an erroneous analysis, as well as not allowing to describe the reality from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará in relation to the efficiency in the use of resources to provide health services. As mentioned in the previous topic, the model to be adopted in the present study was the BCC with Variable Return Scale (VRS) aimed at maximizing products (outputs).

Municipalities of Água Azul do Norte, Canaã dos Carajás, Rio Maria, Santa Maria das Barreiras, Santana do Araguaia, Sapucaia, Tucumã and Xinguara were excluded from the sample, as they did not present data regarding to the production of primary care, and the municipality of Nova Ipixuna, for not presenting data on the number of authorized hospital admissions in 2015. Thus, the final sample was consisted of 30 municipalities from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará. It is important to emphasize that the present study used the variables already observed in studies previously applied in the Brazilian context, with emphasis on Andrade, B. et al. (2017), who used the DEA methodology to assess the efficiency in the use of resources provided by Brazilian capitals to offer health services.

The present study was based, in the selection of variables, on the work developed by Andrade, B. et. al (2017) and will be composed of three input variables: Quantidade de Recursos Humanos – QRH (number of human resources), Quantidade de equipamentos – QEQ (number of equipment) and Quantidade de Estabelecimentos – QES (number of establishments); and three output variables: Autorização de Internações Hospitalares – AIH (authorization for hospital admissions), Produção Ambulatorial – PRA (outpatient production) and Produção da Atenção Básica – PAB (production of primary care). Next, they address the analysis of the inputs, outputs and efficiency results of each municipality.

Table 1 shows the total amount of inputs used by each municipality and the percentage in relation to the total value.

Table 1 –Quantity of inputs (continous)

|

Cities (DMUs) |

QRH - number of human resources |

QEQ - quantity of equipment |

QES - number of establishments |

|||

|

|

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

|

Abel Figueiredo |

1,168 |

0.7% |

456 |

0.56% |

84 |

0.62% |

|

Bancoc |

964 |

0.6% |

766 |

0.94% |

144 |

1.06% |

|

Bom Jesus do Tocantins |

1,378 |

0.8% |

588 |

0.72% |

132 |

0.97% |

|

Brejo Grande do Araguaia |

768 |

0.5% |

72 |

0.09% |

144 |

1.06% |

|

Breu Branco |

3,597 |

2.2% |

1,012 |

1.25% |

340 |

2.50% |

|

Conceição do Araguaia |

6,122 |

3.7% |

1734 |

2.14% |

686 |

5.05% |

|

Cumaru do Norte |

1,244 |

0.8% |

516 |

0.64% |

158 |

1.16% |

|

Curionópolis |

1827 |

1.1% |

1,272 |

1.57% |

156 |

1.15% |

|

Dom Eliseu |

4,641 |

2.8% |

1805 |

2.22% |

322 |

2.37% |

|

Eldorado do Carajás |

3,474 |

2.1% |

516 |

0.64% |

192 |

1.41% |

|

Floresta do Araguaia |

1,735 |

1.1% |

180 |

0.22% |

192 |

1.41% |

|

Jacundá |

4,830 |

2.9% |

1,702 |

2.10% |

305 |

2.24% |

|

Marabá |

34,180 |

20.8% |

12,300 |

15.15% |

2,265 |

16.67% |

|

Novo repartimento |

4,908 |

3.0% |

333 |

0.41% |

439 |

3.23% |

|

Ourilândia do Norte |

3,300 |

2.0% |

1,062 |

1.31% |

419 |

3.08% |

|

Palestina do Pará |

630 |

0.4% |

93 |

0.11% |

110 |

0.81% |

Table 1 – Quantity of inputs (conclusion)

|

Cities (DMUs) |

QRH - number of human Resources |

QEQ – number of equipment |

QES - number of establishments |

|||

|

|

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

|

Goianésia do Pará |

3,176 |

1.9% |

254 |

0.31% |

352 |

2.59% |

|

Itupiranga |

4,009 |

2.4% |

300 |

0.37% |

217 |

1.60% |

|

Paragominas |

12,392 |

7.5% |

10,135 |

12.48% |

1,025 |

7.54% |

|

Paraupebas |

23,073 |

14.0% |

24,624 |

30.33% |

1991 |

14.65% |

|

Pau D'Arco |

1,471 |

0.9% |

1,028 |

1.27% |

132 |

0.97% |

|

Piçarra |

1,491 |

0.9% |

404 |

0.50% |

147 |

1.08% |

|

Redenção |

10,146 |

6.2% |

9,399 |

11.58% |

848 |

6.24% |

|

Rondon do Pará |

3,739 |

2.3% |

1,263 |

1.56% |

371 |

2.73% |

|

São Domingos do Araguaia |

1,609 |

1.0% |

228 |

0.28% |

204 |

1.50% |

|

São Félix do Xingu |

6,368 |

3.9% |

1,404 |

1.73% |

521 |

3.83% |

|

São Geraldo do Araguaia |

1915 |

1.2% |

324 |

0.40% |

260 |

1.91% |

|

São Joao do Araguaia |

1,233 |

0.7% |

133 |

0.16% |

187 |

1.38% |

|

Tucuruí |

15,517 |

9.4% |

6,067 |

7.47% |

1,008 |

7.42% |

|

Ulianópolis |

3,762 |

2.3% |

1,224 |

1.51% |

236 |

1.74% |

|

Total |

164,667 |

100% |

81,194 |

100% |

13,587 |

100% |

Source: Survey data (2021).

In relation to the inputs selected to evaluate the use of resources by the municipalities from the mesoregion do of Southeast Pará, three inputs variables were used: (a)quantity of human resources, composed of professionals with undergraduate, associates, high and middle degrees, both in care and administrative areas ; (b), quantity of equipment, which represents the equipment in use, such as audiology, image diagnosis, dentistry, infrastructure, for life maintenance, by graphic methods, by optical methods, and so on; e (c)number of establishments, which include structures such as the health academy, emergency medical regulation center, hemotherapy and/or hematological care center, psychosocial care center (CAPS ), health center/ basic health unit, pharmacy, specialized hospital, general hospital etc.

Table 2 shows the total amount of health products or services offered by each municipality from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará and the percentage in relation to the total value.

Table 2 –Quantity of products (continuous)

|

Cities (DMUs) |

AIH - authorization for hospital admissions |

PRA – outpatient production |

PAB - production of primary care |

|||

|

|

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

|

Abel Figueiredo |

530 |

0.63% |

111,722 |

0.53% |

23,459 |

1.08% |

|

Bancoc |

306 |

0.36% |

91,359 |

0.43% |

5,661 |

0.26% |

|

Bom Jesus do Tocantins |

1,094 |

1.29% |

129,014 |

0.61% |

28,436 |

1.31% |

|

Brejo Grande do Araguaia |

576 |

0.68% |

71,076 |

0.33% |

17,100 |

0.79% |

|

Breu Branco |

1,144 |

1.35% |

349,082 |

1.64% |

49,200 |

2.26% |

|

Conceição do Araguaia |

4,200 |

4.97% |

1,722,277 |

8.10% |

157,499 |

7.23% |

|

Cumaru do Norte |

470 |

0.56% |

222,710 |

1.05% |

38,131 |

1.75% |

|

Curionópolis |

1,471 |

1.74% |

279,950 |

1.32% |

55,376 |

2.54% |

|

Dom Eliseu |

3,271 |

3.87% |

1,290,336 |

6.07% |

194,315 |

8.92% |

|

Eldorado do Carajás |

2,238 |

2.65% |

491,393 |

2.31% |

23,673 |

1.09% |

|

Floresta doAraguaia |

1,395 |

1.65% |

452,964 |

2.13% |

24,300 |

1.12% |

|

Goianésia do Pará |

1,114 |

1.32% |

340,793 |

1.60% |

17,075 |

0.78% |

|

Itupiranga |

1,404 |

1.66% |

490,668 |

2.31% |

13,558 |

0.62% |

Table 2 – Quantity of products (conclusion)

|

Cities (DMUs) |

AIH - authorization for hospital admissions |

PRA - outpatient production |

PAB - production of primary care |

|||

|

|

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

Abs. |

% |

|

Jacundá |

3,540 |

4.19% |

457,248 |

2.15% |

10,095 |

0.46% |

|

Marabá |

11,995 |

14.18% |

2,188,241 |

10.29% |

59,501 |

2.73% |

|

Novo repartimento |

1935 |

2.29% |

489,795 |

2.30% |

152,411 |

7.00% |

|

Ourilândia do Norte |

2,559 |

3.03% |

493,787 |

2.32% |

55,376 |

2.54% |

|

Palestina do Pará |

277 |

0.33% |

94,008 |

0.44% |

20,272 |

0.93% |

|

Paragominas |

6,037 |

7.14% |

1,377,684 |

6.48% |

131,012 |

6.01% |

|

Paraupebas |

6,597 |

7.80% |

2,718,697 |

12.78% |

126,476 |

5.81% |

|

Pau D'Arco |

522 |

0.62% |

174,212 |

0.82% |

31,661 |

1.45% |

|

Piçarra |

776 |

0.92% |

94,214 |

0.44% |

53,900 |

2.47% |

|

Redenção |

7,952 |

9.40% |

1,949,838 |

9.17% |

80,040 |

3.67% |

|

Rondon do Pará |

7,595 |

8.98% |

495,947 |

2.33% |

116,506 |

5.35% |

|

São Domingos do Araguaia |

701 |

0.83% |

118,452 |

0.56% |

49,779 |

2.29% |

|

São Felix do Xingu |

3,218 |

3.81% |

398,225 |

1.87% |

51,455 |

2.36% |

|

São Geraldo do Araguaia |

2,281 |

2.70% |

294,282 |

1.38% |

88,659 |

4.07% |

|

São Joao do Araguaia |

233 |

0.28% |

193,552 |

0.91% |

42,055 |

1.93% |

|

Tucuruí |

5,937 |

7.02% |

2,882,616 |

13.55% |

260,196 |

11.95% |

|

Ulianópolis |

3,198 |

3.78% |

808,868 |

3.80% |

201,076 |

9.23% |

|

Total |

84,566 |

100% |

21,273,010 |

100% |

2,178,253 |

100% |

Source: Survey data (2021).

Like table 1, table 2 lists the variables in each city and their percentage in relation to the total value. However, the focus is now on the analysis of the products, which are represented by the following variables: authorizations for hospital admissions (AIH), outpatient production (PRA) and number of visits by the Programa Saúde da Família – PSF (Family Health Program), represented by the production of primary care (PAB).

The AIH variable represents the number of authorizations for hospitalization approved throughout 2015, based on the months in which the visits actually took place. These hospitalizations result from various types of medium and high complexity procedures. The variable PRA concerns the number of actions and procedures performed by hospitals in 2015 and approved by the Ministry of Health. These variables can be segregated into the following groups: health promotion and prevention actions; procedures with diagnostic purposes; clinical procedures; surgical procedures; organ, tissue and cell transplants; medicines; orthoses, prostheses and special materials; complementary health care actions.

And the variable PAB is made up of the number of visits by professionals belonging to the PSF in the year 2015. These professionals are segregated into different types of teams, such as: ESF; ESFSB MI; ESFSB MII; EACS; EACSSB MI; EACSSB MII; ESFR; EAB type I; EAB type I SB; ESF type I; ESF type I SB MII; ESF type IV; ESF type IV SB MI; ESF type IV SB MII; transient ESF; transient ESF SB MI; ESF transient SB MII. The selected variables were the same used in the study developed by Andrade, B. et. al (2017).

Based on data referring to the inputs and outputs from each of the DMUs, it was possible to obtain the efficiency index of each city through the application of DEA, as can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3 –Index of municipalities

|

Cities (DMUs) |

Efficiency Index/ Performance (CRS) |

Cities (DMUs) |

Efficiency Index/ Performance (CRS) |

|

Abel Figueiredo |

1 |

Novo Repartimento |

1 |

|

Bancoc |

0.465 |

Ourilândia do Norte |

0.662 |

|

Bom Jesus do Tocantins |

0.771 |

Palestina do Pará |

1 |

|

Brejo Grande do Araguaia |

1 |

Paragominas |

0.804 |

|

Breu Branco |

0.389 |

Paraupebas |

0.975 |

|

Conceição do Araguaia |

1 |

Pau D'Arco |

0.751 |

|

Cumaru do Norte |

0.808 |

Piçarra |

0.77 |

|

Curionópolis |

0.883 |

Redenção |

1 |

|

Dom Eliseu |

1 |

Rondon do Pará |

1 |

|

Eldorado do Carajás |

1 |

São Domingos do Araguaia |

0.784 |

|

Floresta do Araguaia |

1 |

São Félix do Xingu |

0.481 |

|

Goianésia do Pará |

0.688 |

São Geraldo do Araguaia |

1 |

|

Itupiranga |

0.918 |

São Joao do Araguaia |

1 |

|

Jacundá |

0.668 |

Tucuruí |

1 |

|

Marabá |

1 |

Ulianópolis |

1 |

Source: Survey data (2021).

In order to classify the DMUs, statistical methods were adopted, which allowed to elaborate a classification scale from the obtained results. To define which municipalities are classified between weak, good and excellent degree of performance, the cut-off score was defined by subtracting the simple standard deviation from the simple arithmetic average, obtaining the value of 0.677, as can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4 –descriptive analysis

|

Average |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Standard deviation |

Cut |

|

0.861 |

0.389 |

1 |

0.184 |

0.677 |

Source: Survey data (2021).

Based on the cut-off score, the following parameters were defined for classifying the municipalities: (a)weak, if the performance was less than 0.677; (b) good, if the performance is greater than or equal to 0.677 and less than 1; and (c) excellent, if the performance equals to 1. Based on the descriptive analysis of the results obtained, it was possible to classify DMUs according to their degree of efficiency.

Table 5 –Classification of Municipalities according to their degree of efficiency

|

County |

Performance |

County |

Performance |

||

|

Breu Branco |

0.389 |

Weak |

Abel Figueiredo |

1 |

Great |

|

Bancoc |

0.465 |

Weak |

Brejo Grande do Araguaia |

1 |

Great |

|

Sao Felix do Xingu |

0.481 |

Weak |

Conceição do Araguaia |

1 |

Great |

|

Ourilândia do Norte |

0.662 |

Weak |

Dom Eliseu |

1 |

Great |

|

Jacundá |

0.668 |

Weak |

Eldorado do Carajás |

1 |

Great |

|

Goianésia do Pará |

0.688 |

Good |

Floresta do Araguaia |

1 |

Great |

|

Pau D'Arco |

0.751 |

Good |

Marabá |

1 |

Great |

|

Piçarra |

0.770 |

Good |

Novo Repartimento |

1 |

Great |

|

Bom Jesus do Tocantins |

0.771 |

Good |

Palestina do Pará |

1 |

Great |

|

São Domingos do Araguaia |

0.784 |

Good |

Redenção |

1 |

Great |

|

Paragominas |

0.804 |

Good |

Rondon do Pará |

1 |

Great |

|

Cumaru do Norte |

0.808 |

Good |

São Geraldo do Araguaia |

1 |

Great |

|

Curionópolis |

0.883 |

Good |

São Joao do Araguaia |

1 |

Great |

|

Itupiranga |

0.918 |

Good |

Tucuruí |

1 |

Great |

|

Parauapebas |

0.975 |

Good |

Ulianópolis |

1 |

Great |

Source: Survey data (2021).

The results obtained from the data analysis point to the heterogeneity of the efficiency degree of the DMUs, that is, among the studied municipalities, it is noticeable that there is a discrepancy between the relation of available inputs and services offered. However, among the analyzed municipalities, 15 had an excellent degree of efficiency, 10 municipalities had a degree of efficiency classified as good and 5 of the municipalities in the sample had a poor degree of efficiency.

The difference between the degree of efficiency shown between the municipalities is directly related to the ability of each municipality to transforms its resources into health services for the population. In this step, it is verified, according to Machado et al. (2019) and Massuda et al. (2018), the prominent and convergent need of the municipalities work emphatically on efficient and transparent management of public resources aimed at health. It should be noted that the studies presented do not show a causal relationship between investment and quality or equity in public health, since the key point is in the process of managing such resources (Rodrigues, Gontijo, & Gonçalves, 2021).

Municipalities that had an excellent performance proportionately offered more services to the population with less resources, while those that provided more resources than actually services to the population. In order to significantly contribute to public policy actions aimed at improving services provided in inefficient municipalities, Fonseca and Ferreira (2009) point to the exchange of experience between public health managers. Actions can be fostered by institutional relationship networks created by the secretariats of health.

From the results of this study and data presented in the literature, the central idea orbits in the management of resources destined to health. There was no evidence of a univocal relationship between resource volume and efficiency, a corroborated fact in Schneider 's study et al. (2017), in which the US, economically strong, has deficit rates in terms of access and an equitable system.

Viacava et al. (2012) points out as a short-term strategy the creation of intermunicipal health financing to improve the health performance indicators of municipalities, allowing the creation of an institutional relationship network aimed at the elaboration of strategies that aim at greater access of the population to the health services through intercity partnerships.

On the other hand, planning how the municipality's resources will be used in the long-term is a very complicated task for the municipal manager. Uncertainty about success in obtaining new financial resources or even guaranteeing current ones makes decision-making an extremely complex problem, as a wrong choice can lead the municipality to misuse its resources and, consequently, to inefficiency.

This work aimed to measure the technical efficiency of the municipalities from the mesoregion of Southeast Pará in the use of resources to provide health services, and made it possible to identify disparities between the levels of efficiency found, taking as reference the municipalities that make up the mesoregion of Southeast Pará. From the results obtained in the study, it is possible to lead municipal managers to adopt measures, if necessary, of exchange and exchange of experiences, aiming to minimize such discrepancies through not only the better use of productive resources, but above all, the optimization of human efforts in favor of health.

The study identified that there are discrepancies with regard to the provision of public health services between the municipalities of Southeast Pará, and as a suggestion it points to the strengthening of interinstitutional relationships in the elaboration of strategies aimed at greater access of the population to health services through intermunicipal partnerships (Fonseca & Ferreira, 2009). Municipal managers need to seek alternatives through the exchange of experiences and successful alternatives in municipalities close to their context, and through the exchange of knowledge or forming partnerships between municipalities in creating health care networks that guarantee the right access to public health services (Viacava et al., 2012).

As study limitations, it is concluded that DATASUS lacks more recent data. The data measured in 2015 makes clear the information gap of the Public Administration, that makes compromising the information that can subsidize public policies and assertive decision-making. In this step, the delay or even the absence of information about public health services in the municipal scope allows us to envision new opportunities for studies in order to investigate what reasons have taken the delay in updating DATASUS. However, as soon as DATASUS is updated, will serve as a basis for further studies, with the objective of evaluating the evolution in the use of health resources by municipal health managers especially in municipalities located in the state countryside.

Andrade, B. H. S., Serrano, A. L. M., Bastos, R. F. S., & Franco, V. R. (2017). Eficiência do gasto público no âmbito da saúde: uma análise do desempenho das capitais brasileiras. Revista Paranaense de Desenvolvimento, 38(132), 163–179.

Andrade, E. I. G., Acúrcio, F. de A., Cherchiglia, M. L., Belisário, S. A., Guerra Júnior, A. A., Szuster, D. A. C., Faleiros, D. R., Teixeira, H. V., Silva, G. D. da, & Taveira, T. S. (2007). Pesquisa e produção científica em economia da saúde no Brasil. Revista de Administração Pública, 41(2), 211–235.

Banker, R. D., Chang, H., & Cooper, W. W. (1996). Equivalence and implementation of alternative methods for determining returns to scale in data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 89(3), 473–481.

Barros, P. P. (2013). Economia da saúde: conceitos, comportamentos. Coimbra: Edições Almedina.

Brasil. (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/Constituicao.htm

Brasil. (1998). Emenda Constitucional nº 19, de 4 de junho de 1998. Diário Oficial da União. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc19.htm

Brasil. (1990). Lei nº 8.080, de 19 de setembro de 1990. Diário Oficial da União. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8080.htm

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde – DATASUS. (2015a). Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde (CNES). http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?cnes/cnv/equipobr.def

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde – DATASUS. (2015b). Sistema de Informação de Atenção Básica (SIAB). http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?siab/cnv/SIABPPA.def

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde – DATASUS. (2015c). Sistema de Informações Ambulatoriais do SUS (SIA/SUS). http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?sia/cnv/qapa.def

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde – DATASUS. (2015d). Sistema de Informações Hospitalares do SUS (SIH/SUS). http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?sih/cnv/sxuf.def

Casado, F. (2009). Análise envoltória de dados: conceitos, metodologia e estudo da arte na educação superior. Revista Sociais e Humanas, 20(1), 59–71.

Cesconetto, A., Lapa, J. D. S., & Calvo, M. C. M. (2008). Avaliação da eficiência produtiva de hospitais do SUS de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 24, 2407–2417.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2, 429–444.

Fonseca, P. C., & Ferreira, M. A. M. (2009). Investigação dos níveis de eficiência na utilização de recursos no setor de saúde: uma análise das microrregiões de Minas Gerais. Saúde e Sociedade, 18, 199–213.

Giraldes, M. do R. (1995). Distribuição de recursos num sistema público de saúde. In S. F. Piola & S. M. Vianna (Orgs.), Economia da saúde: conceitos e contribuição para a gestão da saúde (pp. 167–190). Brasília: IPEA. https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/livros/CAP7.pdf

Krugman, P. R., & Wells, R. (2007). Introdução à economia. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

Machado, R. C., Forster, A. C., Campos, J. J. B., Martins, M., & Ferreira, J. B. B. (2019). Avaliação de desempenho dos serviços públicos de saúde de um Município paulista de médio porte, Brasil, 2008 a 2015. An Inst Hig Med Trop, Supl. 1, 33–45.

Lins, M. E., Lobo, M. S. de C., Silva, A. C. M. da, Fiszman, R., & Ribeiro, V. J. de P. (2007). O uso da análise envoltória de dados (DEA) para avaliação de hospitais universitários brasileiros. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 12(4), 985–998.

Massuda, A., Hone, T., Leles, F. A. G., Castro, M. C. de, & Atun, R. (2018). The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis and resilience. BMJ Global Health, 3(4), e000829.

Medeiros, D. V. V., & Marcolino, V. A. (2018). A eficiência dos Municípios do Rio de Janeiro no setor de saúde: uma análise através da DEA e regressão logística. Meta: Avaliação, 10(28), 183–210.

Mello, J. C. C. B. S. de, Meza, L. A., Gomes, E. G., Serapião, B. P., & Lins, M. P. E. (2003). Análise de envoltória de dados no estudo da eficiência e dos benchmarks para companhias aéreas brasileiras. Pesquisa Operacional, 23(2), 325–345.

Morais, J. J. (2009). Princípio da eficiência na Administração Pública. Ethos Jus: Revista Acadêmica de Ciências Jurídicas, 3, 99–105.

Nero, C. R. (1995). O que é economia da saúde. In S. F. Piola & S. M. Vianna (Orgs.), Economia da saúde: conceitos e contribuição para a gestão da saúde (pp. 5–23). Brasília: IPEA. https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/livros/CAP1.pdf

Peña, C. R. (2008). Um modelo de avaliação da eficiência da Administração Pública através do método análise envoltória de dados (DEA). Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 12(1), 83–106.

Rodrigues, A. de C., Gontijo, T. S., & Gonçalves, C. A. (2021). Eficiência do gasto público em atenção primária em saúde nos Municípios do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil: escores robustos e seus determinantes. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 26(Supl. 2), 3567–3579.

Rosa, A. R. da. (2018). A busca pela eficiência e os desafios da gestão pública contemporânea: o estudo de caso no Município de Cambuí/MG (Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, Universidade Federal de São João Del-Rei). http://dspace.nead.ufsj.edu.br/trabalhospublicos/handle/123456789/264

Schneider, E. C., Sarnak, D. O., Squires, D., Shah, A., & Doty, M. M. (2017). Mirror, Mirror 2017: international comparison reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health care. The Commonwealth Fund. https://interactives.commonwealthfund.org/2017/july/mirror-mirror/

Soares Filho, A. M., Vasconcelos, C. H., Dias, A. C., Souza, A. C. C., Edgar, M.-H., & Silva, M. R. F. da. (2022). Atenção primária à saúde no Norte e Nordeste do Brasil: mapeando disparidades na distribuição de equipes. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 27(1), 377–386.

Sun, D., Ahn, H., Lievens, T., & Zeng, W. (2017). Evaluation of the performance of national health systems in 2004–2011: An analysis of 173 countries. PLoS ONE, 12(3), e0173346.

Viacava, F., Ugá, M. A. D., Porto, S., Laguardia, J., & Moreira, R. da S. (2012). Avaliação de desempenho de sistemas de saúde: um modelo de análise. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 17, 921–934.

------------

[i] Mestre em Gestão Pública pela UFPE; Doutor em Sociedade, Tecnologias e Políticas Públicas (SOTEPP/ Centro Universitário de Maceió UNIMA); Professor Adjunto da UFCA, Universidade Federal do Cariri.

[ii] Doutor em Matemática pelo PDM, programa de doutorado em matemática com associação ampla UFPA/UFAM. Professor do Curso de Ciências Contábeis da Unifesspa, Universidade Federal do Sul e Sudeste do Pará -Rondon do Pará/PA.

[iii] Graduado em Administração (UNFESSPA); Mestre em Administração (UFSE).

[iv] Mestre e Doutora em Ciência Política pela UFRGS. Professora do Programa de Pós-Graduação em sociedade, Tecnologias e Políticas Públicas (SOTEPP) do Centro Universitário de Maceió (UNIMA).