Bruna Maria Pereira de Pontes, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2886-3719, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. E-mail : brunapontes.99@gmail.com

Nelsio Rodrigues de Abreu, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7024-5642, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. E-mail: nelsio@gmail.com

Resumo

Este artigo buscou compreender como as mulheres com deficiência física vivenciam o processo ritualístico do casamento sob a ótica da vulnerabilidade do consumidor. Foram conduzidas entrevistas semiestruturadas com dez mulheres com deficiência física, as quais vivenciaram essa fase entre os anos 2014 e 2019. As entrevistas foram feitas por chamadas de voz e áudios. Os dados obtidos nas entrevistas foram tratados por análise de conteúdo e as suas categorias foram definidas a priori com base na literatura referente ao consumo simbólico e vulnerabilidade do consumidor. São compreendidos no estudo, os significados, artefatos, momentos e fatores que impulsionam a vulnerabilidade neste contexto. A interpretação dos dados revela que mulheres com deficiência física podem vivenciar dupla vulnerabilidade. No entanto, é importante reconhecer sua capacidade de resiliência.

Palavras-Chave: consumidor com deficiência; vulnerabilidade do consumidor; consumo simbólico.

Abstract

The purpose of this paper was to understand how women with physical disabilities experience the ritualistic process of marriage from the perspective of consumer vulnerability. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten women with physical disabilities. The criteria for their participation were that they would have experienced this phase between the years 2014 and 2019. The interviews were carried out through voice calls and voice messages. The data were treated by content analysis and their categories were previously defined based on the literature regarding symbolic consumption and consumer vulnerability. The meanings, artifacts, moments, and factors that drive consumer vulnerability in this context are understood in the study. The interpretation of the data reveals that women with physical disabilities can experience two forms of vulnerability. However, it is important to recognize that they can present resilience by adapting their experiences. This paper contributes by extending the understanding of consumers with disabilities in an unexplored context of consumption.

Keywords: consumer with disabilities; consumer vulnerability; symbolic consumption.

For a lifetime, individuals experience various changes in roles and phases. These transitions are marked by performic events. Such individuals intend to signal their shifts and consolidate their new identities to the other members of their community (Van Gennep, 1977). To do so, they perform rites and rituals deliberately, loaded with elements, artefacts, script, protagonists, and their audience (Rook, 1985).

According to the magnitude of the ritual in the legitimation of social identities and the demand for the elements that characterize it, symbolic consumption is present, attributing cultural and emotional motivations to what will be consumed, both in artefacts and objects and in the services related to the celebration themselves (Cupollio, Casotti, & Campos, 2013).

Carvalho and Pereira (2014) investigated consumer vulnerability in women's experiences during the injunction of wedding. Thus, vulnerability is concentrated in the individual state (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005). During the transition from bridal to wife, consumers experience a lack of control relationship in their interactions with the market, due to expectations of a perfect day.

Another audience often addressed in vulnerability studies is the consumer with disabilities. In most research, the problem is dealt with from the individual characteristics of people with disabilities, considering accessibility and social issues involving aspects such as discrimination and lack of representativeness (Benjamin et al., 2021; Basu et al., 2023).

Thus, we realize the need for research aimed at the consumption experiences of people with disabilities and the way they make up rituals through ritual consumption. Then comes the guiding question of this research: how do consumers with physical disabilities experience the consumption related to the ritualistic process of wedding? This question considers that brides can be in a state of vulnerability through the transition of social roles and a previous understanding of people with disabilities as potentially vulnerable consumers. Thus, the present research sought to understand how women with physical disabilities experience the ritualistic process of wedding from the perspective of consumer vulnerability.

In addition to this section, this paper is divided into theoretical framework, methodological procedures, analysis of results and final considerations.

There are several moments and roles to be experienced by individuals during life. From birth to death, many events communicate and categorize such identities to be internalized at these stages at the individual and collective level, including rites and rituals (MCcracken, 2003). Van Gennep (1977) categorizes rites on three levels: preliminaries, which correspond to separation rituals; injunctions, transition rituals; and postliminaries, the rituals of incorporation.

The present study approaches the transition ritual, also known as passing. The ceremonies that characterize role changes accompany and dramatize events of greater magnitude, such as death and marriage (Bell, 1997). According to Rook (1985), the rituals have four essential elements for their consummation: the artefacts, the script, the performing roles of the ritual and the audience. All moments and attached objects are intended and follow an organization accepted and built culturally. Thus, ritual consumption incorporates rituals into the conception and use of products, providing new experiences and a sense of control (Wang, Sun, & Kramer, 2021; Song et al., 2022).

These points attribute a symbolic character to the consumption linked to solemnity for legitimation and contextualization of the phases of life (Cupollilo, Casotti, & Campos, 2013). Both positive and negative emotions can boost this trend through various mechanisms (Wang, Sun, & Kramer, 2021; SONG et al., 2022). Specifically in the wedding, various objects carry meanings and importance in the ceremony, such as wedding rings, which give married status (Van Gennep, 1997), and the wedding dress (Min, 2018; Myung & Smith, 2018).

For Sykes and Brace-Govan (2015), the pre-marriage moment would be a rite of passage included in the transitory process itself, as a wife that is not yet established and legitimized. Therefore, the bride is still on a limb between being single and married. This event is linked to the expectation of "Happy Forever", a commitment to life. In addition to the symbolic consumption, it can represent an extraordinary consumer experience. That is because such a ritual is associated with the emotions of their main characters, the bride and groom, in the face of life change, which is in the memory of individuals, contributing significantly to their personal development (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003; Gilovich et al., 2015; Bogdanova & Sirotina, 2023).

Höpner (2017) considers consumer experience to focus on the specific social context of the market in which the consumer lives his experiences. For the unique character, consumption is attributed to a complexity resulting from human, situational and technological variables. Moreover, as the wedding ritual also refers to services, including the choice of the environment for the ceremony, there are other important factors, for example, the physical environment and the atmosphere of the experience (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Wang et al., 2024).

Therefore, in this paper, the wedding ritual is understood as an extraordinary consumer experience, given the importance attributed to this celebration. Moreover, for its consummation, consumption is present symbolically by attributing motivations and meanings to artefacts, moments, and roles. Given the notoriety of consumption at this time, it is necessary to visualize its implications regarding the injunction.

Consumer vulnerability is an impotence from an imbalance in the market or consumption of marketing and product messages (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005). That is, the control of the individual is removed in various consumer situations. This lack of control can result in cases of hostile situations, physical and emotional risk, damage to your psychological well-being and the inability to position yourself in consumer environments (Hill & Sharma, 2020; Salisbury al., 2023).

Hamilton et al. (2015) consider consumer vulnerability as an undesirable state in which affected individuals are exposed to various conditions that challenge participation and reaction to the market. This experience can assume transitional or permanent character (Faria et al., 2017), as in the case of individual states, such as what happens in conspicuous consumption experiences in graduation rituals (Coelho et al., 2017) and the ritualistic wedding process (Carvalho & Pereira, 2014; Bogdanova & Sirotina, 2023).

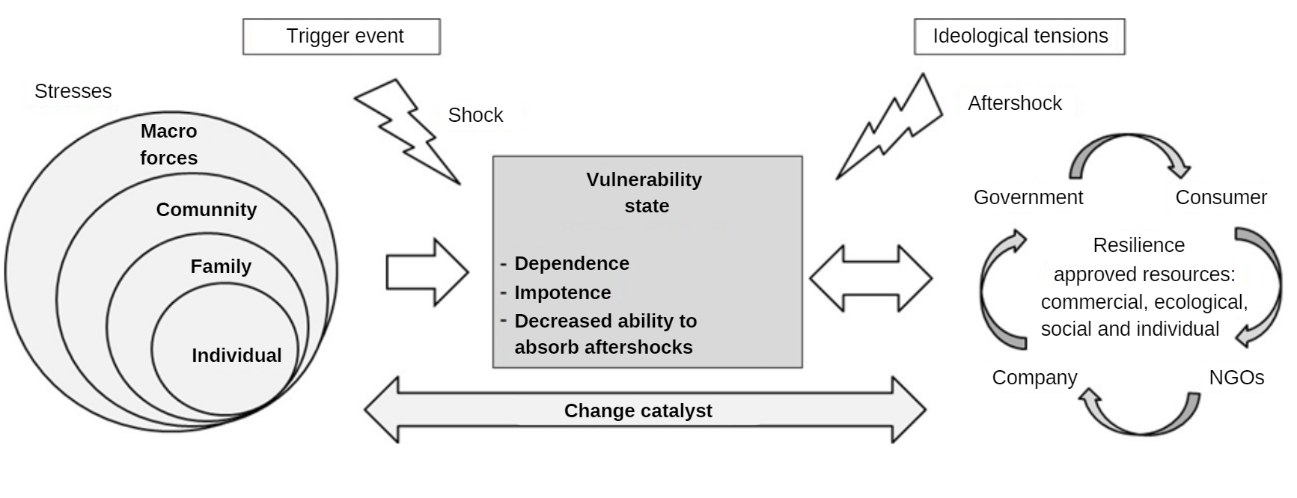

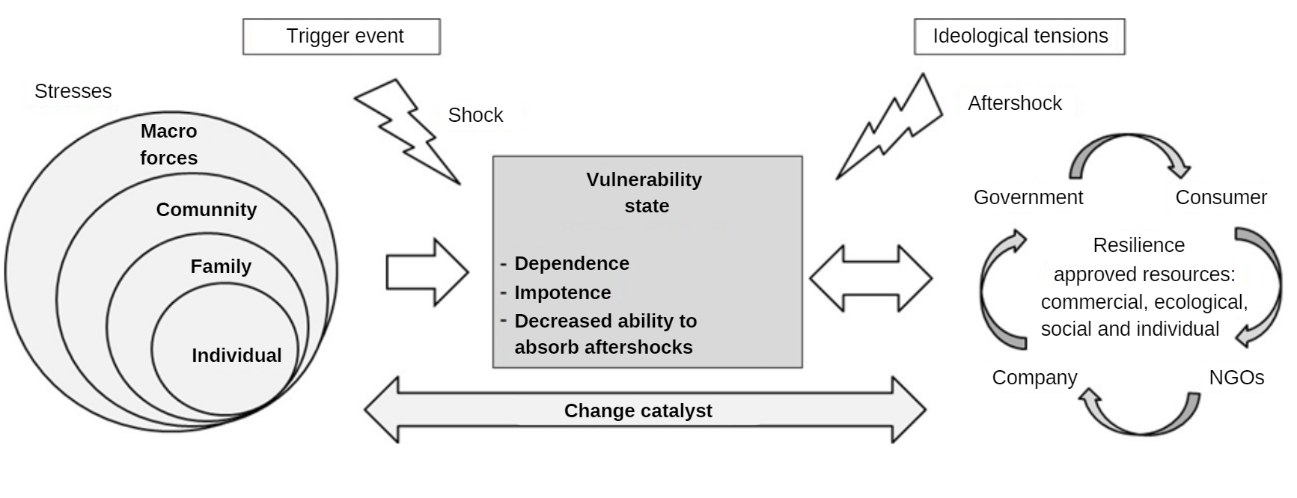

Given the experience of vulnerability, individuals develop mechanisms and ways to overcome or circumvent them and may resign in some cases. In this sense, Baker and Mason (2012) proposed a conceptual model aimed at vulnerability and consumer resilience (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of consumer vulnerability and resilience theory

Source: Adapted from Baker and Mason (2012).

According to Figure 1, there are four determining stresses to the experience of vulnerability, including individual - biophysical and psychosocial characteristics, family, community and macroenvironmental forces - differences between social classes, technology, and others. A trigger event is necessary, that is, a negative event in an individual life, such as the loss of employment, mourning, or accidents, which begins the state of vulnerability through interaction between stresses and such event.

After experiencing vulnerability, it happens an aftershock that corresponds to the acting moment of those involved in overcoming or perpetuating the situation. In search of mitigating or ending vulnerability, NGOs, the government, organizations, and the consumer himself can provide solutions. From that moment on, the consumer resilience process occurs as a reaction to vulnerability.

Marketing studies often address the experience of consumer vulnerability with disabilities, highlighting a tendency and need to explore the experiences and perceptions of these people (Pavia & Mason, 2014). Also noteworthy is the need to understand these individuals in various contexts, and consumer environments, especially those that are part of individual daily life (Lim, 2020; Echeverri & Salomonson, 2024).

In this sense, several researchers seek to understand how people with disabilities consume and their experiences. Celik and Yakut (2021) deal with the relationship between perceived vulnerability and satisfaction in moments of purchases for visually impaired people, as well as demonstrating that these consumers seek normality. Echeverri and Salomonson (2019) sought to understand consumers with disabilities in interactions with mobility services, analyzing the causes, forms, and mechanisms of coping. Thus, human vulnerability can be categorized into three chief forms: physical, psychological, and social, each covering different elements such as genetic predispositions, personality traits and influences of the social context, respectively. At the same time, coping strategies used to face adversities and stresses are classified into four types: problematic, focused on the direct solution of problems; emotional, directed to emotions management; avoidance, which seeks to ignore or deny the stressful situation; and based on social support, which includes the search for foreign aid. The interaction between forms of vulnerability and coping strategies is crucial for developing effective mental health and well-being interventions, pointing out the need for personalized approaches that consider individual peculiarities in coping with challenges (Salomonson, 2019; Juen, Kern, & Thormar, 2023; Orru et al., 2023; Kuhlicke et al., 2023).

In the Brazilian context, Mano (2014) addresses consumers with disabilities in retail environments and points out several limitations and barriers, with an experience in three dimensions: structural, sociocultural, and personal. Faria et al. (2017) investigate consumers' invisibility with Down syndrome starting from the sociocultural environment, from urban mobility to social interactions.

Under the understanding that individual states operate in experimentation with vulnerability, the moment of transition from papers, as in this case, from bride to wife, can also influence this situation of imbalance between it and the market (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005; Hamilton, Dunnet, & Piacentini, 2015; Helberger et al., 2022). Therefore, immersed in their emotions and the search for the perfect day, the consummation of a fairy tale and the social issues that involve this celebration, the bride can make consumer decisions without reasoning and reflectively, based only on emotions.

Upon learning of this, at various times, the bridal market uses mechanisms of influence, as is the case regarding the values of overpriced goods and services or puts the opinion of a ceremonialist, for example, as the main factor when making choices (Carvalho & Pereira, 2014). This same problem occurs in other rituals, whose transitions strikingly present themselves or add a level of social prestige, as in graduations (Coelho et al., 2017).

It is necessary to point out that the discussion about consumer vulnerability does not embrace brides as vulnerable consumers. For Commuri and Eckici (2008), it would be disadvantageous for consumers. That is, these situations alone are not enough to characterize vulnerability. However, the possibility of an imbalance in the consumer relationship is latent.

This research sought to understand how women with physical disabilities experience the ritualistic process of wedding from the perspective of consumer vulnerability. It is a qualitative research developed with women with physical disabilities. Beudaert (2018) exposes the need for studies focusing on the characteristics of consumers with disabilities, such as age, gender, and type of disability. Thus, it was chosen to investigate exclusively women with physical disabilities in the ritualistic process of wedding.

That said, a qualitative approach was more coherent in developing the present study and understanding the phenomenon based on the subjectivities of the living (Flick, 2009). Following this flow, we decided to conduct interviews with a semi-structured script, which is later detailed.

To select the participants, we adopted two criteria: the wedding should have already occurred with the bride-wife transition; a temporal cut of up to 5 years between the time with whom the research was conducted (2021) and the ceremony. About contact with the interviewees, the researcher has searched the Instagram social network through wedding and disability hashtags: #casamentoacessível (accessible wedding), #mulhercomdeficiência (woman with disability) and #acessibilidadeparatodos (accessibility for all). We observed photographs looking for wedding photos or pictures related to the ceremony. Thus, we contacted twenty-six profiles through messages, with a brief presentation and explanation of the research. Sixteen returned the messages, and ten participated in the research, as described in Table 1. At the tenth interview, we perceived a saturation and ceased the process.

Table 1 – Characterization and Profile of the Interviewees

|

Bride |

Age |

Occupation |

Disability cause |

Wedding year |

|

B1 |

40 |

Psychoanalyst |

No Diagnostic |

2015 |

|

B2 |

27 |

Beauty consultant |

Right leg amputation |

2019 |

|

B3 |

31 |

Nutritionist |

Viral Transverse Myilite |

2017 |

|

B4 |

33 |

Banking agent |

Motorcycle accident |

2016 |

|

B5 |

29 |

Attorney |

Car accident |

2017 |

|

B6 |

40 |

Digital media professional |

Shot |

2019 |

|

B7 |

36 |

Administrator |

Car accident |

2014 |

|

B8 |

44 |

Plastic artist |

Progressive muscle dystrophy |

2016 |

|

B9 |

42 |

Housewife |

Motorcycle accident |

2018 |

|

B10 |

25 |

Pedagogue |

Motorcycle accident |

2019 |

Source: author's elaboration (2024).

This study did not use the names of the interviewees to maintain privacy. In addition, to facilitate the analysis and reading process, participants were called B, from 1 to 10. The data were collected by voice calls and voice messages via WhatsApp, according to what participants reckoned more comfortable and accessible. The interviews lasted an average of thirty-three minutes and followed the script displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 – Research script

|

CATEGORY |

DIMENSION |

THEME QUESTION |

|

Symbolic consumption (Rook, 1985; Carvalho & Pereira, 2014) |

Meanings |

|

|

Artefacts |

|

|

|

Moments |

|

|

|

Vulnerability (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005; Mano, 2014)

|

Structural accessibility |

|

|

Sociocultural |

|

|

|

Personal |

|

Source: author's elaboration (2024).

As stated in Table 2, the script was divided into two categories: symbolic consumption and vulnerability. They are dismembered in dimensions that correspond to the relevant aspects of each. Meanings, artefacts, and moments regarding the ritual of wedding and structural accessibility belong to the sociocultural and personal dimensions to understand the vulnerability experience of participants. Sociocultural and personal dimensions of vulnerability correspond to the possibility of transient vulnerability and deficiency.

For data analysis, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the content (BARDIN, 2011) with the following steps: pre-analysis, exploration, and treatment. We treated the data based on the categories and dimensions established in the script, defined a priori. Such characteristics aimed to reduce the chances of biases in the analysis.

This section presents the research results. Data analysis followed the categories and subcategories of the interview script: symbolic consumption (meanings, artefacts, and moments) and consumer vulnerability (structural accessibility and dimensions, sociocultural and personal).

For all participants, the solemnity is considered a significant experience, even before meeting the loved one. B1, for example, reported: "I always wanted to marry, build a family, and everything that understood this universe, I always wanted it." In the same sense, B2 expresses: "Before I even met my husband, I had this interest ... in having a wedding." We also noticed that, after the acquired disability, some participants began to give greater value and attribute meanings to their relationships and phases of life, as shown below:

In fact, no, it wasn't something that I wanted a lot, something I dreamed for myself, "Then I want to marry white in the church and such." No, I had none of that, occasionally, my husband and I, we even considered the possibility, but nothing serious, you know. I just commented like this and let it pass. Oh, when I accident, I started thinking about a lot of things like that we leave for later, you know: when it comes, when there is time left, when we left time... and we move on, you know? [...] (B7)

It is possible to see that, in the face of a life-changing event, the experience of disability can provide the search for extraordinary new consumer experiences (Höpner, 2017).

The consummation of ceremonies that signal transitions and aggregations to the individuals' identity needs planning and attention, given their uniqueness or rareness throughout life (Van Gennep, 1977; Bell, 1997). Thus, the ritual must meet the expectations. Regarding wedding, in general, various aspects demand attention, including the objects used in the ritual, the buffet and the wedding venue (Carvalho & Pereira, 2014).

Considering this, we asked the interviewees about the decisions and criteria taken in the event planning. In addition to the points raised in the study by Carvalho and Pereira (2014), accessibility emerged as a major concern, which emphasizes the reality of consumers with disabilities in finding accessible environments capable of providing them with satisfactory consumption experiences (Mano, 2014; Paiva & Mason, 2014). Such concern is explicit in the quotes below.

I think the aspects I took into consideration was an accessible place that had no religious nature. It was hard to find a place that had a bathroom, that I could enter, that was prepared to receive a wheelchair user person (B6).

The choice of the place was something that we worried a lot about accessibility and a not large space, because there were not so many guests (B9).

After choosing a place with accessibility, the concern with the ceremony budget was something important to most brides: “So, as it is wedding, I was a little worried, right ... because everything seems to be more expensive” (B2); “Number of guests, limit spending, finding a place, decoration, buffet, all these things” (B5). Another aspect is the cost-benefit question, in which they seek to ensure that their expectations were met as genuinely as possible, which is expressed in B3's speech: “I wanted to do my best of what I had in mind, I had some wishes, and I tried to get the best suppliers according to what I had devised. ” Therefore, we understand that the relevance to the celebration of the ceremony depends on three factors: accessibility, financial factors, and the satisfaction of expectation.

Based on the rituals' elements proposed by Rook (1985), we sought to understand the role of objects and artefacts at the wedding ceremony. For the interviewees, the object of the highest emotional value is the wedding ring. The dress (Min, 2018; Myung & Smith, 2018) is also an object that carries great meaning for them. Another crucial point about the dress is its comfort:

In the case of the dress, I had a tough time choosing it. I had a lot of difficulty with the tests. Then as I didn't like any, it was hard to wear. So, I had to have a dress, especially for myself. I went to a store and set up one for me. So, in the same way, they passed me the value. I don't know if a person without disabilities would have any difference in cost (B1).

The wedding dress was one of the things, I mean, I had never worn a dress like that, you know. So, I thought so what like “How uncomfortable to put, pulling (B8).

So ... I didn't have that thing, putting the dress dreamed, because I had to choose something that adapted to that situation ... (B7).

Look, not everything works out being a wheelchair, for example, dress, I ended up having it. So, I wear a diaper and suddenly cucumber, and I get all dirty there (B6).

We notice the same reality of other consumer contexts experienced by people with disabilities: the difficulty in finding adapted goods and services (Dubost, 2018). In this case, the dress, one of the crucial artefacts for people without disabilities, with enormous commotion (Carvalho & Pereira, 2014), which is worrying and difficult for respondents.

Regarding the wedding moments, the entry of the wedding rings and the bridal entry have great significance to the research participants. In addition, other moments are created by the bride and the groom, such as the sand ceremony to symbolize the union itself and other important people, such as the wedding party (B6).

The entrance of the wedding rings, in my mind, should be my grandmother and my grandfather entering the rings, the oldest people in my family, who had a longtime marriage entering the rings. However, my grandmother passed away a year before the wedding [...]. So, I wondered how I would replace my grandmother at that moment. She was irreplaceable [...] My younger cousin came in with the wedding rings. He had three to four years [...] that moment was so special that it seemed she was there. Everyone cried in the church. (B3)

My entry into the church, surely, no doubt ... The moment when all eyes turned to me, and my husband, the groom at the time, was there, with his eyes shining ... my family too and all the important people ... There was no greater emotion. (B10)

The consumer experience in this context is subjective. Artefacts, objects, and moments play a significant role in characterizing the ceremony itself. Another point is the importance of the audience and other participants in the ritual (Van Gennep, 1997), who also react, thrill and are added to the ritual. In the graduation context, addressed by Coelho et al. (2017), the largest role of these participants is financial, being actually emotional, helping to build the experience.

From the perspective that transient states can also interfere with the experimentation of consumer vulnerability (Coelho et al., 2017; Carvalho & Pereira, 2014) and that consumers with disabilities face several structural and social barriers that put them in imbalance before the market (Baker et al., 2005; Hamilton et al., 2015), this part of data analysis is centred on double vulnerability: consumer vulnerability with disabilities and transient state, expressed in the following subtopics.

Initially, we sought to understand about structural accessibility (Mano, 2014) when choosing environments for the wedding. Thus, participants punctuated the lack of accessibility not only in environments related to the ceremony but also in other consumer environments, such as beauty salons and dress stores.

I wanted to marry in a church that was important to me all my life and that I thought so, very cute, very cozy. So, I already knew, right? It was in a Franciscan convent church. So, there is already an idea, all cute, all little. In the parts that was not accessible, I talked to the administrators, the nuns. Where there was no accessibility, I made it accessible, which was crucial to me [...]. (B1)

So, I got married in the church. And the church is not accessible. I don't know if you are Catholic, but the church has the altar that always has steps. So, I needed a ramp. I had to talk to the priest to make this ramp. (B3)

In these transcripts, the accessibility conditions in the churches are precarious, providing a condition of consumer vulnerability (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005). However, participants seek to circumvent such a problem by contacting those responsible for the environments with the resilience experience (Baker & Mason, 2012). As for environments aimed at the bridal market, there is the same problem.

I was concerned about the accessibility of where I rent the dress. There was no accessibility for the dress proof which was upstairs, but the designer was committed to bringing me there in his arms. The whole team was very gentle. (B2)

Some places I would like to go, and I couldn't because of accessibility. There were some places where I was looking for dresses, and I saw beautiful dresses on the showcase, but the bridal section was on the second floor and had no elevator. There was nothing. And then they told me: "Oh, but what model do you want? We can bring it." And, damn, there is no model you want. We looked and that's it. We must prove it. So, I didn't have that possibility. (B7)

It is difficult to find an accessible hall. In the city where I live, most places are not accessible, especially for the brides. It was not exactly accessible since the hall is only ground floor. But the part of the bride is often at the top of the hall. So, it was challenging to find one that was more ground floor, but there were two steps. Then the hairdresser made the ramp, so I didn't have to climb the steps. (B3)

I live in a small city. So, I didn't have many possibilities. I was organizing remotely. I hired a ceremonialist, and I valued the accessibility of the confectionery, the place for me to get ready, the venue, accessibility. (B10)

Based on this, we realize that research participants in this ambience are not perceived as consumers, given the companies' disregard for providing them with accessible environments. This corroborates with Silva et al. (2015) in their study of accessibility in the hotel environment. The vulnerability of consumers with disabilities does not arise from disability, but it is due to lack of accessibility, which demonstrates the lack of consideration of this public's needs.

In addition, unpreparedness is not only in the lack of structural accessibility but also in the lack of attention to the individual's needs, for example, in the way they deal with the disabled or reduced mobility.

Service providers are not prepared to deal with a population with disabilities or have any movement limitations. For example, on my wedding day, one of the guests has limited locomotion and walks with a cane, an elderly gentleman, and I am a wheelchair user. The ceremonialist made the guest go to me with the utmost difficulty. (B5)

Based on the above, it is possible to visualize how women with disabilities in this consumer context are in an unbalanced relationship with the market since the whole problem begins with the basics: the lack of accessibility. Moreover, as vulnerability is understood in other dimensions, they are treated in the following subsections, which concern attitudinal points and relations between people with disabilities with consumer environments and aspects related to self-esteem and self-identity as consumer deficiency.

As for interactions with organizations regarding the ritual's celebration, the interviewees point to the search to work with ceremonialists, advisors, suppliers, and other service providers they already knew and trusted. Such a concern is expressed by B1: "I sought people I already knew and already knew me, and we already had some friendship." Still in this topic, given the factors that drive the experience of consumer vulnerability, we also sought to understand whether participants somehow found themselves in a situation of discrimination or ableism (Baker, Genty, & Rittenburg, 2005). That said, none of them pointed out any situation that made them vulnerable at the attitudinal level.

We had no problem with sellers or suppliers about discrimination. It was all good. As it was a different thing, they were super excited. As it was a birthday and a wedding, they were super excited. It was very nice. (B10)

No, I think it was nice, satisfactorily. He had no difficulty because he is a wheelchair user. The problem is lack of accessibility in the places. For example, in the hall that I went to get ready, I had no accessibility. If it were today, I would change places. But it is difficult to find any. The problem is structural accessibility. But I had no problem for disability. (B5)

In addition, B3 added: "I would not hire the company if I knew or was a victim of anything like that." Moments later, during the interview, she addressed the need for understanding by companies about the ability of people with disabilities as a consumer.

Regardless of being wheelchair users or having a disability, we are still consumers. We can consume even more. I wanted to my wedding different things. So, we need to demystify that wheelchair users are not consumers. We are a consumer audience, who performs, who does. I think this, which came to mind now, because, I don't know, people tend to think about people with disabilities as "poor", who are not idealistic, don't consume, don't buy, you can't sell to PWD. And it's not like that. PWD has as much access as or even more than people who can walk. So, it's balanced. (B3)

There is a constant concern for people with disabilities about whether consumers can enjoy most consumption experiences, which corroborates Goodrich and Ramsey (2011). Thus, there is a lack of market consideration about the needs and expectations of consumers (BENJAMIN et al., 2021).

Given the possibility of the experience of a vulnerable consumption by the transition of social roles, we sought to understand the experience of brides with the whole ceremony. Given the importance of this ritual for the interviewees, most of them pointed to anxiety as one of the main feelings experienced throughout the process. Many choices were based mainly on emotions (Carvalho & Pereira, 2014), seeking the perfect day. One of the interviewees summarizes well the interviewees' perception of vulnerability in the face of wedding

As a bride, a lot of anxiety and insecurity. Because I had never stopped to look at the wedding as one of those who hope to be doing it one day. So, I never paid much attention to the details and such. So, I was unsure if it was going to be beautiful if it would work. I was extremely amazed at the prices of everything because it's absurdly expensive, right, get married. Also because I didn't even know how much I could spend since the groom had not said "ok", right? (B7)

Like B7, they all punctuated anxiety as the main feeling and that they would change things in their ceremonies, including B3, who married without the help of an advisor. After the planning experience, she understood the importance since all obligations and decisions were hers, without any support. B5 was supported by a ceremonialist, but she felt deceived, when part of the decoration was not as planned by the ceremonialist: “I asked for natural flowers in the altar decoration, and when I saw, I knew no They were ... and like, I paid for them. ” B2 also reported problems regarding the ceremony: "I see that these difficulties were not for personal reasons, for my disability, but for their lack of professionalism." B5 and B3 corroborate with the study of Carvalho and Pereira (2014) by demonstrating a situation that creates an imbalance between brides and the market. In addition, concern for price and feelings such as insecurity and anxiety also correspond to the findings of Carvalho and Pereira (2014).

In addition, some participants thought of limiting the financial value of the ritual. Some of them stated they would not renounce some artefacts, objects, and services to accomplish their dreams, as declared by B3: “There are no limits to accomplishing a dream. Sometimes, the limitation is how we see the situation and the limits we put ourselves. Everything is possible with willpower and effort. ” B9 also talked about the search to perform his expectations and showed regret when she did not.

I called the flower shop, I called the ceremonialist, right, and asked to change the flowers, even paying much more expensive, because I'm sure that I would regret it if I had not done it, as I regret some other details, like the dress. I thought about changing some things and said: "Oh, I won't be boring to change now, right." I didn't change, and I regret it today. (B9)

Given the understanding that consumer vulnerability challenges consumer experiences, we sought to understand whether the disability had any implication in the ceremony (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, 2005; Hamilton, Dunnet, & Piacentini., 2015).

I don't think so because I did everything I wished. I danced [...] So, I consider that everything I would do if I walked, I did, in a different way. In this case, I danced in the chair, but anyway. I think there was nothing, no factor that could have influenced this. (B3)

No. I was even afraid of not working, but it worked! The bride's day was on the top floor, and my brother had to bring me in his arms. But I found it beautiful. It is a memory of a dream accomplished. Other people contributed to making it special, regardless of my limitations. (B4)

Participants showed that the experience was not compromised at all. When they realized any problem, they sought alternatives to ensure that the moment was kept as desired (Baker & Mason, 2012). This finding agrees with Echeverri and Solomonson (2019), in the context of mobility services. The way these consumers deal with negative situations is subjective and may be proactive or reactive. Therefore, research participants can experience the vulnerability of both forms: due to the individual state and disability. There was a lack of knowledge about the bridal market and its practices and barriers imposed on disability, especially on a structural level.

This paper sought to understand how women with physical disabilities experience the ritualistic process of the wedding from the perspective of consumer vulnerability. The data show that women with physical disabilities can experience vulnerability in wedding planning in two ways: by the individual state and disability. The first reason is due to the transition from paper, bride to wife, and for the importance socially attributed to the wedding. As for disability, the possibility of vulnerability is due to the accessibility of physical environments, clothing and the ableist and discriminatory vision still strong in society.

Participants understand that they are consumers potentially vulnerable for both reasons. Because they know the possibility, they often present themselves proactively and resiliently, anticipating responses to situations of vulnerability or giving a new meaning to some moments. Thus, the wedding market must adopt a proactive approach to inclusion, developing business and service practices that transcend the mere reaction to the needs of consumers with disabilities. These practices should identify and eliminate potential barriers, preventing them from becoming significant impediments. This effort reflects an understanding of the vulnerabilities faced by consumers with disabilities, who often come across obstacles not only physical but also social and emotional, in access to goods and services in the bridal market.

Reconfigure marketing strategies to portray women with disabilities authentically and respectfully not only addresses these vulnerabilities but also celebrates the resilience of these consumers. Resilience, understood here as the ability to overcome challenges and barriers, should be recognized and valued in product and service development. Thus, involving consumers with disabilities directly in the creative process. It is not only a matter of inclusion but also an opportunity to capture and incorporate resilience into innovations that benefit the entire market.

This focus not only satisfies the specific needs of this group but enriches the market with new perspectives and innovative solutions. Therefore, the commitment to research and continuous development is vital to ensure the offer of products that are not only affordable but also reflect the latest trends of fashion and meet the expectations of brides with disabilities. Thus, by recognizing vulnerability and fostering resilience, the wedding market can become truly inclusive, offering significant and valuable experiences for all brides.

As for the limitations of the study, the research planned to conduct research with women experiencing the transitory wedding process. However, due to the pandemic scenario, we could not find women with this profile. Another point is that different types of disability can present the possibility of vulnerability in other forms. With these limitations, we suggest developing studies with women experiencing this process. In addition, during analysis and reflections, new insights emerged for studies, such as studying consumers with disabilities in beauty and leisure services.

Baker, S. M., Gentry, J. W., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2005). Building understanding of the domain of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(2), 128–139.

Baker, S., & Mason, M. (2012). Toward a process theory of consumer vulnerability and resilience: Illuminating its transformative potential. In D. Mick, S. Pettigrew, C. Pechmann, & J. Ozanne (Eds.), Transformative consumer research for personal and collective well being: Reviews and frontiers (pp. xx–xx). New York: Routledge.

Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70.

Basu, R., Kumar, A., & Kumar, S. (2023). Twenty‐five years of consumer vulnerability research: Critical insights and future directions. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(1), 673–695.

Bell, C. (1997). Ritual: Perspectives and dimensions. Oxford University Press.

Benjamin, S., Bottone, E., & Lee, M. (2021). Beyond accessibility: Exploring the representation of people with disabilities in tourism promotional materials. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2), 295–313.

Beudaert, A. (2018). Towards an embodied understanding of consumers with disabilities: Insights from the field of disability studies. Consumption Markets & Culture, 23(4), xx–xx.

Bogdanova, M. V., & Sirotina, I. L. (2023). The semiotic space of wedding rituals: Religious canon and socio-cultural context. Izvestiya of the Samara Russian Academy of Sciences Scientific Center. Social, Humanitarian, Medicobiological Sciences, 25(2), 36–43.

Carvalho, D., & Pereira, R. (2014). De solteira a casada: O consumo vulnerável das mulheres durante a transição liminar do casamento. In Anais do VI Encontro da Divisão de Marketing da ANPAD, 6, 1–16.

Celik, A. A., & Yakut, E. (2021). Consumers with vulnerabilities: In-store satisfaction of visually impaired and legally blind. Journal of Services Marketing, 35(6), 821–833.

Coelho, P., Orsini, A., Brandão, W., & Pereira, R. (2017). A vulnerabilidade e o consumo conspícuo no ritual de formatura. Revista Interdisciplinar de Marketing, 7(1), xx–xx.

Commuri, S., & Ekici, A. (2008). An enlargement of the notion of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(2), 183–186.

Cupollilo, M., Casotti, L., & Campos, R. (2013). Estudos de consumo: Um convite para a riqueza e para a simplicidade da pesquisa de rituais brasileiros. ADM.MADE, 17(3), 27–46.

Dubost, N. (2018). Disability and consumption: A state of the art. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 33(2), xx–xx.

Echeverri, P., & Salomonson, N. (2019). Consumer vulnerability during mobility service interactions: Causes, forms and coping. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(3–4), 364–389.

Faria, M., Casotti, L., & Carvalho, J. (2017). Vulnerabilidade e invisibilidade: Um estudo com consumidores com síndrome de Down. Gestão & Regionalidade, 34(100), 203–217.

Gilovich, T., Kumar, A., & Jampol, L. (2015). A wonderful life: Experiential consumption and the pursuit of happiness. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 5(1), xx–xx.

Goodrich, K., & Ramsey, R. (2011). Are consumers with disabilities receiving the services they need? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(1), 88–97.

Hamilton, K., Dunnett, S., & Piacentini, M. (2015). Introduction. In Consumer vulnerability: Conditions, contexts and characteristics (pp. 1–10). London: Routledge.

Helberger, N., et al. (2022). Choice architectures in the digital economy: Towards a new understanding of digital vulnerability. Journal of Consumer Policy, 45, 1–26.

Höpner, A. (2017). Construção da experiência de consumo: Um olhar para compreender o valor nas experiências (Tese de Doutorado, PUCRS, Porto Alegre).

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

Kuhlicke, C., et al. (2023). Spinning in circles? A systematic review on the role of theory in social vulnerability, resilience and adaptation research. Global Environmental Change, 80, 102672.

Juen, B., Kern, E., & Thormar, S. B. (2023). Individual and organizational vulnerability and resilience factors in the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1216698.

Lim, J. (2020). Understanding the discrimination experienced by customers with disabilities in the tourism and hospitality industry: The case of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability, 12(18), xx–xx.

Mano, R. (2014). Consumidor com deficiência: Implicações de fatores pessoais e contextuais no consumo varejista de João Pessoa/PB (Dissertação de Mestrado, UFPB, João Pessoa).

McCracken, G. (2003). Cultura e consumo (1ª ed.). São Paulo.

Min, S., Ceballos, L., & Yurchisin, J. (2018). Role power dynamics within the bridal gown selection process. Fashion and Textiles, 5(17), xx–xx.

Myung, E., & Smith, K. (2018). Understanding wedding preferences of the millennial generation. Event Management, 22(1), xx–xx.

Orru, K., et al. (2023). Imagining and assessing future risks: A dynamic scenario‐based social vulnerability analysis framework for disaster planning and response. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 31(4), 995–1008.

Pavia, T., & Mason, M. (2014). Vulnerability and physical, cognitive, and behavioral impairment: Model extensions and open questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 34, 47–xx.

Rook, D. W. (1985). The ritual dimension of consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 251–264.

Salisbury, L., et al. (2023). Beyond income: Dynamic consumer financial vulnerability. Journal of Marketing, 87(5), 657–678.

Salomonson, N., & Echeverri, P. (2024). Embodied interaction: A turn to better understand disabling marketplaces and consumer vulnerability. Journal of Marketing Management, 1–40.

Song, W., et al. (2022). How positive and negative emotions promote ritualistic consumption through different mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 901572.

Sykes, K., & Brace-Govan, J. (2015). The bride who decides: Feminine rituals of bridal gown purchase as a rite of passage. Australasian Marketing Journal, 23(1), xx–xx.

Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), xx–xx.

Van Gennep, A. (1977). The rites of passage (Reprinted ed.). London: Routledge.

Wang, L., et al. (2024). Does the well-matched marriage of successor affect the intergenerational inheritance of family business? Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–10.

Wang, X., Sun, Y., & K. T. (2021). Ritualistic consumption decreases loneliness by increasing meaning. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(2), 282–298.